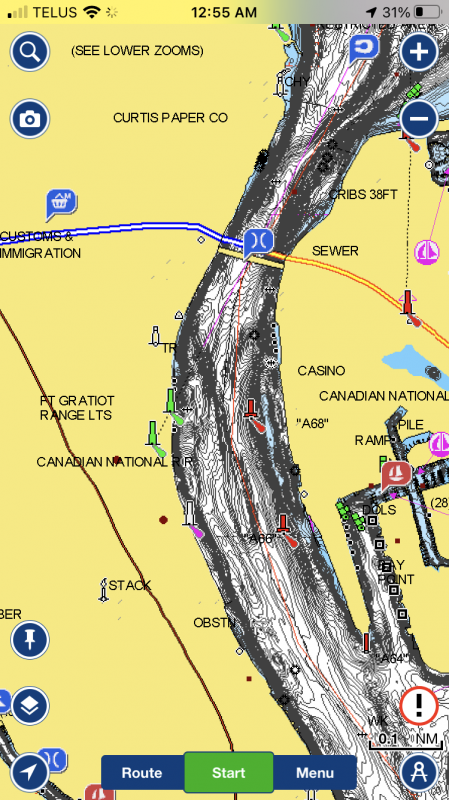

This is the active shipping channel in the St Clair River at Sarnia. The current is quite strong. Freighters do pass each other in the St Clair River farther downstream of the curve at Sarnia.

After an accident in the 1970s a system was worked out for freighters at the curve in the River at the Bluewater Bridge.

“As the lights of the ship and nearby Port Huron sparkled on the inky black water at 1:46 a.m. June 5, the current below the Blue Water Bridge caught the Smith in a cold death grip, turning the helpless vessel broadside in the channel, directly in the path of the downbound Canadian steamer Parker Evans of the Hindman fleet.

Propellers on both vessels thrashed vainly at the water in an effort to avoid disaster and, in a cacophony of tortured steel, the bow of the heavily loaded Evans plunged into the Smith's starboard side, flooding the Smith with thousands of tons of river water.

The Evans staggered off to shore and anchored, seriously damaged but unwilling to sink.

Within 20 minutes, however, the mortally wounded Smith rolled over on her starboard side in approximately 40 feet of water, but not before the crew of the Port Huron pilot boat Sally M. had plucked the Smith's entire crew from the rapidly sinking vessel. This was a feat for which the pilot boat crew would later receive several lifesaving awards from the U.S. Coast Guard.

As the wrecked Smith was in the shipping channel, vessel traffic was halted, then restricted to one-way travel in the days following the sinking.

The heavy current undermined the underwater bank upon which the Smith rested, causing the hull to break and separate on June 7 and creating the potential for environmental damage from leaking oil. Erie Sand abandoned the wreck on June 20 and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers started a massive salvage effort.

Divers pumped out her bunker oil and separated the two hull sections with cutting torches and dynamite. The bow and stern were raised in the summer and fall of 1972, the cabins and machinery removed and both sections later towed to Sarnia where they were filled in together become a dock.

Total salvage cost was $5 million.

In October 1972, shipping companies agreed to one-way alternating traffic between buoys one and two north of the Blue Water Bridge and the Black River to avoid having vessels pass in the tricky current.

Also created as a result of the collision was the Sarnia Traffic Centre.

Operated by the Canadian Coast Guard, the centre provides Vessel Traffic Services, or VTS, for commercial vessels over 20 meters (approximately 65 ½ feet) in length in the region from lower Lake Huron to western Lake Erie.

As vessels traverse the area, they are required to call in at certain checkpoints and give their estimated times of arrival for the next checkpoint, allowing Sarnia Traffic, other vessels and boatwatchers to keep tabs on the whereabouts of all vessel traffic in the region, much like air traffic controllers at a major airport.

Today, the Smith's remains are still located just south of the grain elevator and Sarnia Government dock, directly across from Port Huron. The dock is known simply as the Sidney Smith dock or just simply the Smith dock, a sad end for the once-proud vessel.

Her loss was not in vain, however, as ship captains today can concentrate on navigating the treacherous currents near the Blue Water Bridges without other vessels nearby, a much safer arrangement than on that dark June night almost 40 years ago”

The story of the steamer Sidney E. Smith, Jr.

After an accident in the 1970s a system was worked out for freighters at the curve in the River at the Bluewater Bridge.

“As the lights of the ship and nearby Port Huron sparkled on the inky black water at 1:46 a.m. June 5, the current below the Blue Water Bridge caught the Smith in a cold death grip, turning the helpless vessel broadside in the channel, directly in the path of the downbound Canadian steamer Parker Evans of the Hindman fleet.

Propellers on both vessels thrashed vainly at the water in an effort to avoid disaster and, in a cacophony of tortured steel, the bow of the heavily loaded Evans plunged into the Smith's starboard side, flooding the Smith with thousands of tons of river water.

The Evans staggered off to shore and anchored, seriously damaged but unwilling to sink.

Within 20 minutes, however, the mortally wounded Smith rolled over on her starboard side in approximately 40 feet of water, but not before the crew of the Port Huron pilot boat Sally M. had plucked the Smith's entire crew from the rapidly sinking vessel. This was a feat for which the pilot boat crew would later receive several lifesaving awards from the U.S. Coast Guard.

As the wrecked Smith was in the shipping channel, vessel traffic was halted, then restricted to one-way travel in the days following the sinking.

The heavy current undermined the underwater bank upon which the Smith rested, causing the hull to break and separate on June 7 and creating the potential for environmental damage from leaking oil. Erie Sand abandoned the wreck on June 20 and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers started a massive salvage effort.

Divers pumped out her bunker oil and separated the two hull sections with cutting torches and dynamite. The bow and stern were raised in the summer and fall of 1972, the cabins and machinery removed and both sections later towed to Sarnia where they were filled in together become a dock.

Total salvage cost was $5 million.

In October 1972, shipping companies agreed to one-way alternating traffic between buoys one and two north of the Blue Water Bridge and the Black River to avoid having vessels pass in the tricky current.

Also created as a result of the collision was the Sarnia Traffic Centre.

Operated by the Canadian Coast Guard, the centre provides Vessel Traffic Services, or VTS, for commercial vessels over 20 meters (approximately 65 ½ feet) in length in the region from lower Lake Huron to western Lake Erie.

As vessels traverse the area, they are required to call in at certain checkpoints and give their estimated times of arrival for the next checkpoint, allowing Sarnia Traffic, other vessels and boatwatchers to keep tabs on the whereabouts of all vessel traffic in the region, much like air traffic controllers at a major airport.

Today, the Smith's remains are still located just south of the grain elevator and Sarnia Government dock, directly across from Port Huron. The dock is known simply as the Sidney Smith dock or just simply the Smith dock, a sad end for the once-proud vessel.

Her loss was not in vain, however, as ship captains today can concentrate on navigating the treacherous currents near the Blue Water Bridges without other vessels nearby, a much safer arrangement than on that dark June night almost 40 years ago”

The story of the steamer Sidney E. Smith, Jr.