DIVE DRY WITH DR. BILL #699: THE NESTING INSTINCT

As a young naturalist growing up in the suburbs of Chicago, I spent many afternoons hiking the fields and creeks of my hometown looking for critters like snakes, turtles, insects and rabbits. The only sport I was really good at was swimming and that season was in the depths of winter when temperatures were quite chilly and snow piled high and deep. Summer swim season involved early morning and late afternoon practices so I was still free to wander quite a bit.

I knew the names of many of our local critters. I collected insects and even had a small zoo in my parent's garage that I charged a nickel for the other kids to see. That ended when my pet mice escaped the cage and Mom freaked out. For some strange reason I never was very keen on birds, but occasionally enjoyed watching the eggs hatch in their nests and the parents feeding them.

In today's column I'll focus on a nest of a different "color..." that of our state salt water fish, the garibaldi (Hypsypops rubicundus). Like many other fish species, the male does all the hard work of nest building and defense. I guess that frees the ladies to focus their energy on producing batches of healthy eggs to lay in them. Males are also rather promiscuous and may "entertain" several females in their nest, so no self-respecting lady wants to help out for the sake of her competitors.

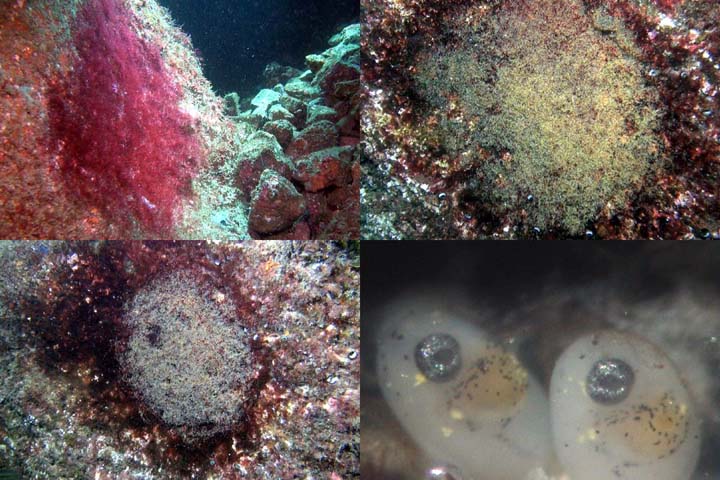

I have read that the males start getting the urge around March and begin farming their nests. They do so by removing all seaweed except certain species of red algae from a patch on the reef. Thus a garibaldi nest looks red (or very dark if there is little light) before any eggs are laid in it. These nest sites within their territory may be used year after year.

The ladies start feeling their oats (or is it algae?) when water temperatures reach about 58-59° F. She leaves her territory and seeks out males with suitable nests. When the male sees her, he begins swimming in circles (not unlike many human males I've observed in our local bars). This pattern of swimming in large ovals is referred to as "dipping." To make sure she gets the message, he produces a clicking sound by grinding his teeth. In humans that usually causes the lady to leave the bedroom, but it seems to work for these fish.

The female often seeks out males with nests that already have young eggs in them. She will then lay her yellow eggs close to those of the previous female. Therefore, garibaldi nests with recently laid eggs have large patches of yellow. These patches will increase in number as new females add theirs to the nest over a period of a week or two. Dr. Milton Love states that males more vigorously defend nests with a larger number of clutches.

As the eggs develop, the embryos are a gray color with dark eyes. This causes the clutches of maturing eggs to turn from yellow to gray. Often one will see nests with clutches of both yellow and gray eggs in them. Eggs hatch within two to three weeks depending on water temperature. This occurs shortly after sunset. The newly emerged larvae swim toward the surface to begin a planktonic stage filled with travel (dispersal) and adventure (avoiding getting munched if possible).

Once all eggs in a male's nest have hatched, the nest is once again red in color. The male begins the process all over, attempting to attract new females into his lair and vigorously defending the new eggs. He may go through as many as four such brood cycles in a season. No wonder the poor guys are all tuckered out at the end of summer!

© 2016 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of nearly 700 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Fresh garibaldi nest (red), with newly-laid eggs (yellow); with maturing eggs (gray) and image of developing embryos under microscope.

As a young naturalist growing up in the suburbs of Chicago, I spent many afternoons hiking the fields and creeks of my hometown looking for critters like snakes, turtles, insects and rabbits. The only sport I was really good at was swimming and that season was in the depths of winter when temperatures were quite chilly and snow piled high and deep. Summer swim season involved early morning and late afternoon practices so I was still free to wander quite a bit.

I knew the names of many of our local critters. I collected insects and even had a small zoo in my parent's garage that I charged a nickel for the other kids to see. That ended when my pet mice escaped the cage and Mom freaked out. For some strange reason I never was very keen on birds, but occasionally enjoyed watching the eggs hatch in their nests and the parents feeding them.

In today's column I'll focus on a nest of a different "color..." that of our state salt water fish, the garibaldi (Hypsypops rubicundus). Like many other fish species, the male does all the hard work of nest building and defense. I guess that frees the ladies to focus their energy on producing batches of healthy eggs to lay in them. Males are also rather promiscuous and may "entertain" several females in their nest, so no self-respecting lady wants to help out for the sake of her competitors.

I have read that the males start getting the urge around March and begin farming their nests. They do so by removing all seaweed except certain species of red algae from a patch on the reef. Thus a garibaldi nest looks red (or very dark if there is little light) before any eggs are laid in it. These nest sites within their territory may be used year after year.

The ladies start feeling their oats (or is it algae?) when water temperatures reach about 58-59° F. She leaves her territory and seeks out males with suitable nests. When the male sees her, he begins swimming in circles (not unlike many human males I've observed in our local bars). This pattern of swimming in large ovals is referred to as "dipping." To make sure she gets the message, he produces a clicking sound by grinding his teeth. In humans that usually causes the lady to leave the bedroom, but it seems to work for these fish.

The female often seeks out males with nests that already have young eggs in them. She will then lay her yellow eggs close to those of the previous female. Therefore, garibaldi nests with recently laid eggs have large patches of yellow. These patches will increase in number as new females add theirs to the nest over a period of a week or two. Dr. Milton Love states that males more vigorously defend nests with a larger number of clutches.

As the eggs develop, the embryos are a gray color with dark eyes. This causes the clutches of maturing eggs to turn from yellow to gray. Often one will see nests with clutches of both yellow and gray eggs in them. Eggs hatch within two to three weeks depending on water temperature. This occurs shortly after sunset. The newly emerged larvae swim toward the surface to begin a planktonic stage filled with travel (dispersal) and adventure (avoiding getting munched if possible).

Once all eggs in a male's nest have hatched, the nest is once again red in color. The male begins the process all over, attempting to attract new females into his lair and vigorously defending the new eggs. He may go through as many as four such brood cycles in a season. No wonder the poor guys are all tuckered out at the end of summer!

© 2016 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of nearly 700 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Fresh garibaldi nest (red), with newly-laid eggs (yellow); with maturing eggs (gray) and image of developing embryos under microscope.