As you said repeatedly throughout the reset of the thread, you did not actually say that a diver should hold the breath during the ascent, but that is what most people would infer from what you wrote. I sure did, and that is after rereading it after your strongly worded attacks on the reading ability of those who said you did.

A joint DAN/PADI study on dive fatalities found that an air embolism following a rapid ascent to the surface (with the diver obviously holding the breath) is the number one incident-related reason for dive fatalities.

That is why I am so obsessed with two things I see repeated over and over and over and over on ScubaBoard (including this thread):

It would be really hard to get to the surface in an out of air emergency.Your ability to get to the surface in an out of air emergency depends upon your ability to hold your breath.

Here is the reality:

- Training for escape from submarines has had sailors successfully reach the surface from 300 feet, starting after they exhale first and then continuing to exhale all the way to the surface.

- If you are exhaling all the way to the surface, your ability to hold your breath has zero, nada, nil, nothing to do with your ability to get to the surface.

(jcr: emphasis added and subtracted [the strikethrough is for incorrect concepts, as enunciated by BoulderJohn])

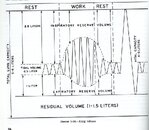

Okay, I'm replying to this post by BoulderJohn so as to bring this back to the discussion. I fully agree. Before doing that, I'd like to review with people this diagram from the

U.S. Navy Diving Manual, March 1970. If you look at this

Figure 1-24. Lung volume, you can see our normal "tidal volume" showing at about 0.5 liters. This is for normal breathing, which is what we teach for scuba diving. So if in my experiment I exhaled and could not inhale, the "expiratory reserve volume" still in my lungs is about 1 liter. I did my comparison from 75 feet, which is just over 3 atmospheres (66 feet, or 20 meters, is 3 atmospheres absolute pressure). What does this mean. Well, that 1 liter, upon ascending from that depth, will expand to over 4 liters of air by the time I reach the surface. Note that a normal person has a 4-5 liter vital capacity (mine is closer to 6 liters.) Actually, in my test in 16 feet of water, I did get expansion so as to never have a problem exhaling. Note that 4 liters is 8 times the amount of a normal breath, which like I said is what we teach divers to do while breathing.

I learned diving in 1959 from the book by J.Y. Cousteau titled

The Silent World. I read that book probably 3 times when it was the only reference I had to learn diving physics and physiology. If you read that book, Cousteau introduces you to Archimedes Principle in the first chapter, when he states on page 4:

The diving lung was designedh to be slightly buoyant. I reclined in the chilly water to estimate my compliance with Archimedes' principle that a solid body immersed in liquid is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the liquid displaced. Dumas justified me with Archimedes by attaching seven pounds of lead to my belt. I sank gently to the sand. I breathed sweet effortless air. Tthere was a faint whistle when I inhaled and a light rippling sound of bubbles when I breathed out. The regulator was adjusting pressure precisely to my needs...(page 4-5)

Cousteau introduced me to much of my understanding of physics and physiology as a 13 year-old boy. The same is true of his discussion of pressure, and he explained the way that Frédérick Dumas trained the first French divers to train on the aqualung.

...Dumas planned the diving courses for the fleet aqualung divers, two of whom are to be carried on each French naval vessel. He immerses the novices first in shallow water to bring them through the fetal stage that took us years--that of seeing through the clear window of the mask, experiencing the ease of automatic breathing, and learning that useless motion is the enemy of undersea swimming. On his second dive the trainee descends fifty feet on a rope and returns, getting a sense of pressure change and testing his ears. The instructor startles the class with the third lesson. The students go down with heavy weights and sit on the floor fifty feet down. The teacher remoses his mask and passes it around the circle. He molds the mask again, full of water. One strong nasal exhalation blows all the water through the flanges of the mask. Then he bids the novices emulate him. They learn that it is easy to stop off their nasal passages while the mask is off and breathe as usual through the mouthgrip.

A subsequent lesson finds the class convened at the bottom and again their attendance is assured by weights. The professor removes his mask. Then he removes his mouthpiece, throws the breathing tube look back over his head and unbuckles the aqualung harness. He lays all his diving equipment on the sand and stands, naked except for his breechclout. With sure, unhurred gestures he resumes the equipment, blowing his mask and swallowing the cupful of water in the breathing tubes. The demonstration is not difficult for a person who can hold a lungful of air for a half minute.

By this time the scholars realize they are learning by example. They remove their diving equipment entirely, put itback on, and await the praise of the teacher. The next problem is that of removing all equipment and exchanging it among each other. People who do this gain confidence in their ability to live under the sea.

At the end of the course the honor students swim down to a hundred feet, remove all equypment and return to the surface naked. The baccalaureate is an enjoyable rite. As they soar with their original lungful, the air expands progressively in the journey through lessening pressures, issuing a continuous stream of bubbles from puckered lips...(JY Cousteau, with Frédéric Dumas, The Silent World, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, Copyright 1953, pages 179-80.)

Note that the original diving course, by Frédérick Dumas, involved a graduation by a relaxed swimming ascent without a dive lung from 100 feet (30.5 meters). I have no doubt that, at age 77, I could complete a CESA from the limit of sport diving, 130 feet (40 meters). "This baccalaureate is an enjoyable rite"! This is not an emergency ascent, but a controlled swimming ascent from 100 feet depth to the surface. From the description, it sounds like it was a relaxed swimming ascent without fins too! This is some of the history of scuba diving that has been lost for this generation of both students and instructors.

Again, this is for sport diving, without incurring a decompression obligation, and not being in an overhead environment (wreck, cave, under ice, etc.) diving.

SeaRat