El Graduado

Contributor

- Messages

- 833

- Reaction score

- 1,666

The Birth of the Cruise Ship Industry, Part 1

Copyright 2012, Ric Hajovsky

When did the Cruise Ship Industry begin? If you guessed the 1920s, guess again. 1820s? Not even close. The Cruise Ship business was well established and functioning in the mid-1300s. That date is not a typographical error; there were cruise ships plying the Mediterranean in the 14th century! They were well organized, money-making machines that took the pious European pilgrims to the Holy Land.

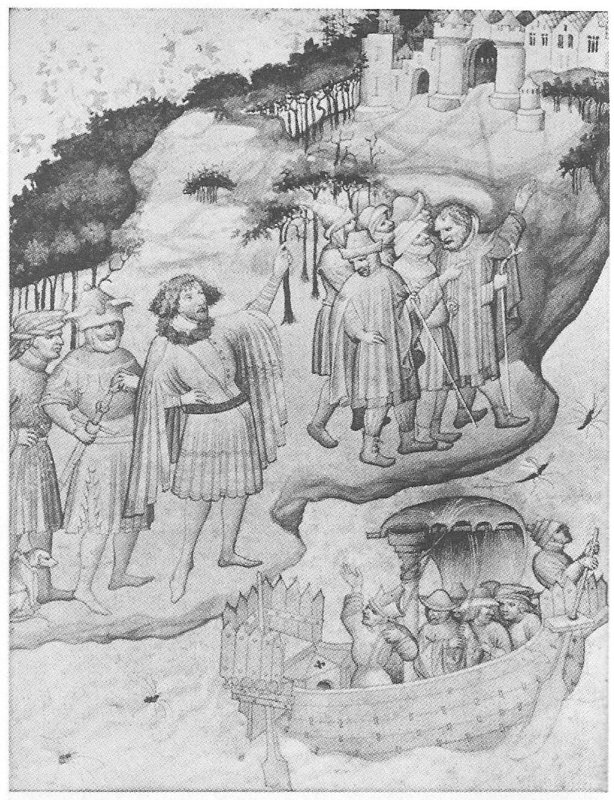

Above: “Cruise ship” passengers beginning their “shore excursion” in the Holy land from Sir John Maudevile’s (Mandeville) 15th century book.

The urge to visit the sacred cities and villages of the Bible was just as strong then as it is today; perhaps even stronger. Intrepid travelers would gather their funds, convert them to gold or bills of exchange, and begin to make their way to Venice, where the galleys (ships with both oars and sails) were waiting for the start of tourist season (between April and June) to begin their voyages to what is now Israel. The pilgrims and tourists who made it safely to Venice were accosted by touts who would surround them, shouting and waving arms to get their attention, each one extolling the virtues of the inn he was representing. They worked on commission, of course. Eventually, the weary travelers would find their way to their respective quarters, where they soon would be cornered by the next round of salespeople. These were the ships’ representatives, each telling their prospective clients about how luxurious his galley was and how dangerous all the others were. These men all offered a standardized contract that had been approved by the Venice government. It provided, for a negotiated fee, the travelers’ sea transport to the Holy Land and back to Venice, two meals a day “fit for human consumption,” the cost of their inns in the Holy land, ground transport (i.e. donkeys) to the sites to be visited, admission fees to the sites (collected by the “Saracens,” or Muslims, who now ruled the area), and the cost of the tour guides (however, the contract specifically excluded the guides’ tips). First class accommodation aboard was, of course, more expensive. The equivalent of “Tourist Class” was no more than an 18-inch-wide by 5-foot-long space outlined in chalk on the floor deck below the rowing deck of the galley. That deck had no portholes. There, one could spread out one’s mattress or bedroll and try to ignore the din of snores, coughs, and other bodily sounds emanating from your fellow passengers for the next few weeks. Light and air came in only through the hatchways. Persons booking this class of service were prohibited from going on the top deck while the galley was at sea. Bribes were, of course, accepted to allow one to get around this prohibition.

The heat and stench below decks was nearly intolerable, and the space was full of rats, lice, fleas, and other disease-carrying vectors. Not a few pilgrims died along the way. The contract stipulated that anyone dying at sea was to be dumped overboard and their possessions guarded by the captain until the galley returned to Venice, where they would be made available to the next-of-kin. The contract also stipulated that each galley must have a company of no less than 20 cross-bowmen aboard to fend off pirates.

There were several “Rough Guides to Traveling to the Holy Land” available for purchase. One, Iteneraries to Jerusalem, printed by William Wey in 1458, suggested that one go to the shop near St. Mark’s and buy “a fedyr bedde, a matres, too pylwys, too peyre schetis, and a qwylt” and sell them again for half price when you return to Venice. Wey noted that although meals were included, “ye schal oft tyme have need to yowre vytels” and so it was wise to bring along your own snacks.

When all the berths on the galleys were finally sold out, the ships would make their way slowly towards Jaffa, their port-of-call in the Holy Land. Seigneur D’Anglure, in his guidebook Le Saint Voyage de Jherusalem, printed in 1395, remarks that the city was fine and large, but uninhabited. The Saracens knew how to run a port-of-call. No galleys were allowed to let their passengers disembark just anywhere they pleased; the pilgrims were confined to the old abandoned port city of Jaffa, now repurposed into a canton where the Europeans could be controlled and herded much easier than in an actual working port city. From the moment the tourists disembarked, their board, lodgings, excursions, tours, guides, and whole timetable was strictly arranged. There were hundreds of sites to see and they only had three weeks to see them all. The Jerusalem Journey, as it was called in the 14th and 15th centuries, was basically accomplished at a dead run.

Copyright 2012, Ric Hajovsky

When did the Cruise Ship Industry begin? If you guessed the 1920s, guess again. 1820s? Not even close. The Cruise Ship business was well established and functioning in the mid-1300s. That date is not a typographical error; there were cruise ships plying the Mediterranean in the 14th century! They were well organized, money-making machines that took the pious European pilgrims to the Holy Land.

Above: “Cruise ship” passengers beginning their “shore excursion” in the Holy land from Sir John Maudevile’s (Mandeville) 15th century book.

The urge to visit the sacred cities and villages of the Bible was just as strong then as it is today; perhaps even stronger. Intrepid travelers would gather their funds, convert them to gold or bills of exchange, and begin to make their way to Venice, where the galleys (ships with both oars and sails) were waiting for the start of tourist season (between April and June) to begin their voyages to what is now Israel. The pilgrims and tourists who made it safely to Venice were accosted by touts who would surround them, shouting and waving arms to get their attention, each one extolling the virtues of the inn he was representing. They worked on commission, of course. Eventually, the weary travelers would find their way to their respective quarters, where they soon would be cornered by the next round of salespeople. These were the ships’ representatives, each telling their prospective clients about how luxurious his galley was and how dangerous all the others were. These men all offered a standardized contract that had been approved by the Venice government. It provided, for a negotiated fee, the travelers’ sea transport to the Holy Land and back to Venice, two meals a day “fit for human consumption,” the cost of their inns in the Holy land, ground transport (i.e. donkeys) to the sites to be visited, admission fees to the sites (collected by the “Saracens,” or Muslims, who now ruled the area), and the cost of the tour guides (however, the contract specifically excluded the guides’ tips). First class accommodation aboard was, of course, more expensive. The equivalent of “Tourist Class” was no more than an 18-inch-wide by 5-foot-long space outlined in chalk on the floor deck below the rowing deck of the galley. That deck had no portholes. There, one could spread out one’s mattress or bedroll and try to ignore the din of snores, coughs, and other bodily sounds emanating from your fellow passengers for the next few weeks. Light and air came in only through the hatchways. Persons booking this class of service were prohibited from going on the top deck while the galley was at sea. Bribes were, of course, accepted to allow one to get around this prohibition.

The heat and stench below decks was nearly intolerable, and the space was full of rats, lice, fleas, and other disease-carrying vectors. Not a few pilgrims died along the way. The contract stipulated that anyone dying at sea was to be dumped overboard and their possessions guarded by the captain until the galley returned to Venice, where they would be made available to the next-of-kin. The contract also stipulated that each galley must have a company of no less than 20 cross-bowmen aboard to fend off pirates.

There were several “Rough Guides to Traveling to the Holy Land” available for purchase. One, Iteneraries to Jerusalem, printed by William Wey in 1458, suggested that one go to the shop near St. Mark’s and buy “a fedyr bedde, a matres, too pylwys, too peyre schetis, and a qwylt” and sell them again for half price when you return to Venice. Wey noted that although meals were included, “ye schal oft tyme have need to yowre vytels” and so it was wise to bring along your own snacks.

When all the berths on the galleys were finally sold out, the ships would make their way slowly towards Jaffa, their port-of-call in the Holy Land. Seigneur D’Anglure, in his guidebook Le Saint Voyage de Jherusalem, printed in 1395, remarks that the city was fine and large, but uninhabited. The Saracens knew how to run a port-of-call. No galleys were allowed to let their passengers disembark just anywhere they pleased; the pilgrims were confined to the old abandoned port city of Jaffa, now repurposed into a canton where the Europeans could be controlled and herded much easier than in an actual working port city. From the moment the tourists disembarked, their board, lodgings, excursions, tours, guides, and whole timetable was strictly arranged. There were hundreds of sites to see and they only had three weeks to see them all. The Jerusalem Journey, as it was called in the 14th and 15th centuries, was basically accomplished at a dead run.