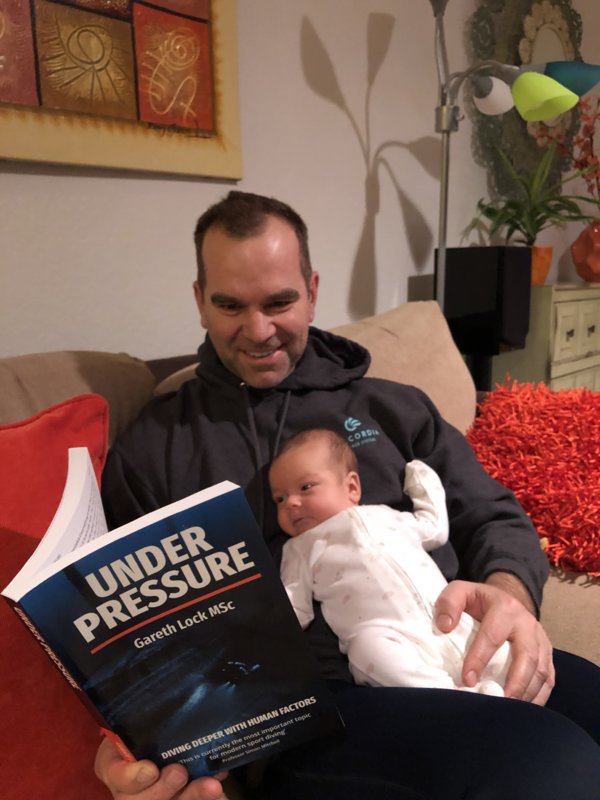

My daughter really liked it.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Under Pressure: Diving Deeper with Human Factors - audiobook

- Thread starter king_of_battle

- Start date

Please register or login

Welcome to ScubaBoard, the world's largest scuba diving community. Registration is not required to read the forums, but we encourage you to join. Joining has its benefits and enables you to participate in the discussions.

Benefits of registering include

- Ability to post and comment on topics and discussions.

- A Free photo gallery to share your dive photos with the world.

- You can make this box go away

Oh. That's so cute.My daughter really liked it.

View attachment 563472

A very nice review. Thank you @king_of_battle.I haven't written a book review in a while so be kind....

TL;DR On a star rating system I gave it 4 of 5 stars. The narrator was a little fast. The content timely and compelling. I wish he had spent more time talking about how to change the culture in diving. I would recommend to any divers.

I finished listening to the book on audible this afternoon on my way home from work. I'll briefly touch on the audio content then jump into the content of the actual book. I ended up buying the ebook and audiobook through amazon. As @Marie13 said above there are a few tables but nothing crazy. The narrator does a good job describing them and I referenced them later when I wasn't driving.

The narrator was a little fast for me but manageable with audible's speed settings. I normally listen to books at 1.5x but dropped it down to 1.25x for him to sound 'normal' to me. Unsurprisingly (as @Compressor mentioned) he spoke with a British accent but it was clear to my Texan ears. Sound mixing probably could have been a hair better - a few places they dubbed over were louder than the bulk of the book but not a major distraction. Overall no complaints with the narrators performance.

A quick background about me - I'm in the pharmaceutical industry and my current role has me heavily involved in continuous improvement and trying to deploy human performance principles to our management teams on down to the manufacturing floor. My industry is moving away from 'human error' and agencies like the FDA are becoming less accepting of that as a root cause to manufacturing issues - which is a great trend. A lot of what Gareth talks about wasn't new to me but it was interesting seeing its deployment to a different yet familiar environment.

The book builds on itself explaining one principle and then using that as a building block for the next component. Each chapter has at least one case study that highlights the principles of the chapter. It flowed well and didn't force you to jump around much (the exception could be if you wanted to review an earlier case study to re-examine it based on later chapter principles). The way I view the book is it starts by giving you the right language to understand Human Performance (HuP) then guides you from looking internally, for example how we understand our role in risk analysis, to a more external view; just culture and how we view the risks others took. To me the book follows this internal/external mindset of first looking at how we view the principles in ourselves and then how we take that into a team/organizational setting. I thought that was a great way to communicate the ideas and effectively showed how bias can play into perception of events.

I also enjoyed his discussions on teamwork and what that means. He reiterated several times the differences between 'buddy teams' and teams demonstrating teamwork. I know I've been guilty of mistaking one for the other and developing that team mentality is something I'll work on with several of the people I consistently dive with.

I also liked that he spent a chapter talking about failure. Failure scares the hell out of me but he hit the nail on the head that we learn the most from the things we fail to do. When I was in the army I failed air assault school because I didn't pay enough attention to properly staging a HMMWV to be sling loaded. Specifically I missed a roll of duct tape sitting on a wheel and that one front window pane had an 'x' of tape across only the outside, not both the inside and outside. It was awful. But once I accepted the failure and reflected on it I gained more from that then I ever would have from completing the course (we were heavy artillery - a helicopter isn't moving my paladin). I gained a new found respect for situational awareness and taking time to understand my surroundings before jumping into anything. This has served me well both in my post army career and my diving. I am happy that he brings this topic up and spends a chapter on it. All too often failures are hidden and the opportunities that could come from them are lost. Hopefully this starts a trend.

Which leads me to my one real criticism of the book. I wish there had been more discussion on how to implement these principles in the larger diving scene. It feels like a chapter is missing from the book. Beyond role modeling best behaviors there isn't really a discussion on changing the culture as a whole. Gareth reflects on several industries that are highly regulated (energy, aviation, healthcare) that have government over site, mandates, and - to some degree - legal protection that allows more open discussion without the fear of reprisal. Diving has none of that. Instructors, dive buddies, etc. have no protection if discussing their part in an accident no matter how minor. I'm not sure how we as divers will open up and conduct widespread accident analysis without it nor did it seem like Gareth had an answer to that either. I agree we have to start somewhere and the people who opened up with the case studies are a huge leap in the right direction however I'm not sure if we are moving significantly closer to a tipping point in the industry that allows the frank and honest discussions that are needed to better the sport.

By no means do I want to dissuaded anyone from reading the book. If you internalize the lessons and build the capabilities out with your team you'll gain soft skills that are rarely taught in diving that can also be used in many professional settings. Y'all will become a more cohesive and responsive team. You can be safer. This is an area largely ignored in the diving community and I'm glad this book is out there fostering discussion. Until we have a workable solution to true accident analysis it will take individuals being brave enough to withstand potential criticism and open themselves up by explaining what went wrong and the context that lead to that event. As Gareth said - we don't choose to make a mistake. Understanding the chain of events culminating in the accident, especially as perceived by the divers at those moments, is critical to us making the sport safer, accidents and failures becoming learning opportunities, and everyone becoming better divers.

king_of_battle

Contributor

Thanks! I really hope the book and thoughts behind it gain traction in the industry. I would consider this book as impactful as books dealing with technical skills such as "Deco for Divers" and "The Six Skills".

I encourage all my students to read the book before class, and think that the introduction of Human Factors is the biggest game changer in the industry in the last 10 years. $40 spent on the book is about as good as it gets in terms of "bang for your buck" to make you a better and safer diver.

@king_of_battle thanks for the review.

I agree that writing something about trying to change the industry would be useful. However, given that the book is already 110k words long and at normal 1x audible speed is 11.5 hrs, I didn't think adding something more would help given that the industry itself is focused on making money and performance & safety standards are, in the main, given a second seat.

If the industry was seriously interested in improving diving safety, by looking at both the technical aspects of diving as well as the non-technical (social, cultural, non-technical and human factors), it would invest in better research into why incidents and accidents occur and change the conditions in which diving takes place. As Prof James Reason said, "You can't change the human condition, but you can change the condition in which humans work" meaning that we can't change our innate human behaviour, so it is much better to focus on the things which shape and influence human behaviour and change those.

The way the industry manages risk is via primarily risk transference to the lowest levels possible, be that diver, instructor or dive centre. The agencies and manufacturers isolate themselves from the risk through waivers and compliance-based activities. In the current litigious society we live in, I can totally sympathise with the way they are managing risk. However, that doesn't help divers themselves manage risk (or more correctly, uncertainty).

I believe there is a significant paradox when it comes to applying regulations, rules and procedures within the diving industry - "Those who had the near-misses, incidents, accidents should have been following the rules" and yet "I don't want to have to follow rules because it is an adventurous sport and there is always going to be a risk. If you don't understand the risk, don't take part." One of my students summed up the challenge faced when trying to bring human factors, non-technical skills and a Just Culture into the diving industry as

"The problem with bringing human factors into the diving industry IS human factors."

Regulation is not the answer, and neither is designing systems which infer near-perfect human performance. As such, training doesn't deal with the inevitable human performance variability (initial and drift over time) which we all struggle with on a daily basis. Until we, as a diving community, truly accept and understand 'human error', the opportunity to develop a Just Culture is very limited, and without a Just Culture in place, learning from failure is not effective because the focus is on negative outcomes rather than how it made sense to those involved.

Finally, another reason for not dealing with this topic directly, is that I would have opened myself up to specific challenges when criticising specific parts of the industry. To make specific challenges, I would need to have had rock-solid evidence of failures at the organisational and supervisory levels, with a confidence that could be defended in a court of law, and that is missing in many cases. As such, I didn't talk about that even though there are lots of papers written in other industries (which aren't regulated) about how to create change. The key attribute for those organisations who achieved change in safety and performance was that their leadership was focused on making the change and it was commercially viable to do so. In diving, creating wholesale change is expensive and you have to recoup that somehow. The general metric of safety in diving is based around the number of dead divers and law-suits. In the grand scheme of things, there aren't too many of those, fortunately.

Just after I pushed 'Send', this appeared in my Facebook feed and sums up the problem.

"People make errors, which lead to accidents. Accidents lead to deaths. The standard solution is to blame the people involved. If we find out who made the errors and punish them, we solve the problem, right? Wrong. The problem is seldom the fault of an individual; it is the fault of the system. Change the people without changing the system and the problems will continue"

Don Norman - Design of Everyday Things

I agree that writing something about trying to change the industry would be useful. However, given that the book is already 110k words long and at normal 1x audible speed is 11.5 hrs, I didn't think adding something more would help given that the industry itself is focused on making money and performance & safety standards are, in the main, given a second seat.

If the industry was seriously interested in improving diving safety, by looking at both the technical aspects of diving as well as the non-technical (social, cultural, non-technical and human factors), it would invest in better research into why incidents and accidents occur and change the conditions in which diving takes place. As Prof James Reason said, "You can't change the human condition, but you can change the condition in which humans work" meaning that we can't change our innate human behaviour, so it is much better to focus on the things which shape and influence human behaviour and change those.

The way the industry manages risk is via primarily risk transference to the lowest levels possible, be that diver, instructor or dive centre. The agencies and manufacturers isolate themselves from the risk through waivers and compliance-based activities. In the current litigious society we live in, I can totally sympathise with the way they are managing risk. However, that doesn't help divers themselves manage risk (or more correctly, uncertainty).

I believe there is a significant paradox when it comes to applying regulations, rules and procedures within the diving industry - "Those who had the near-misses, incidents, accidents should have been following the rules" and yet "I don't want to have to follow rules because it is an adventurous sport and there is always going to be a risk. If you don't understand the risk, don't take part." One of my students summed up the challenge faced when trying to bring human factors, non-technical skills and a Just Culture into the diving industry as

"The problem with bringing human factors into the diving industry IS human factors."

Regulation is not the answer, and neither is designing systems which infer near-perfect human performance. As such, training doesn't deal with the inevitable human performance variability (initial and drift over time) which we all struggle with on a daily basis. Until we, as a diving community, truly accept and understand 'human error', the opportunity to develop a Just Culture is very limited, and without a Just Culture in place, learning from failure is not effective because the focus is on negative outcomes rather than how it made sense to those involved.

Finally, another reason for not dealing with this topic directly, is that I would have opened myself up to specific challenges when criticising specific parts of the industry. To make specific challenges, I would need to have had rock-solid evidence of failures at the organisational and supervisory levels, with a confidence that could be defended in a court of law, and that is missing in many cases. As such, I didn't talk about that even though there are lots of papers written in other industries (which aren't regulated) about how to create change. The key attribute for those organisations who achieved change in safety and performance was that their leadership was focused on making the change and it was commercially viable to do so. In diving, creating wholesale change is expensive and you have to recoup that somehow. The general metric of safety in diving is based around the number of dead divers and law-suits. In the grand scheme of things, there aren't too many of those, fortunately.

Just after I pushed 'Send', this appeared in my Facebook feed and sums up the problem.

"People make errors, which lead to accidents. Accidents lead to deaths. The standard solution is to blame the people involved. If we find out who made the errors and punish them, we solve the problem, right? Wrong. The problem is seldom the fault of an individual; it is the fault of the system. Change the people without changing the system and the problems will continue"

Don Norman - Design of Everyday Things

@king_of_battle thanks for the review.

I agree that writing something about trying to change the industry would be useful. However, given that the book is already 110k words long and at normal 1x audible speed is 11.5 hrs, I didn't think adding something more would help given that the industry itself is focused on making money and performance & safety standards are, in the main, given a second seat.

If the industry was seriously interested in improving diving safety, by looking at both the technical aspects of diving as well as the non-technical (social, cultural, non-technical and human factors), it would invest in better research into why incidents and accidents occur and change the conditions in which diving takes place. As Prof James Reason said, "You can't change the human condition, but you can change the condition in which humans work" meaning that we can't change our innate human behaviour, so it is much better to focus on the things which shape and influence human behaviour and change those.

The way the industry manages risk is via primarily risk transference to the lowest levels possible, be that diver, instructor or dive centre. The agencies and manufacturers isolate themselves from the risk through waivers and compliance-based activities. In the current litigious society we live in, I can totally sympathise with the way they are managing risk. However, that doesn't help divers themselves manage risk (or more correctly, uncertainty).

I believe there is a significant paradox when it comes to applying regulations, rules and procedures within the diving industry - "Those who had the near-misses, incidents, accidents should have been following the rules" and yet "I don't want to have to follow rules because it is an adventurous sport and there is always going to be a risk. If you don't understand the risk, don't take part." One of my students summed up the challenge faced when trying to bring human factors, non-technical skills and a Just Culture into the diving industry as

"The problem with bringing human factors into the diving industry IS human factors."

Regulation is not the answer, and neither is designing systems which infer near-perfect human performance. As such, training doesn't deal with the inevitable human performance variability (initial and drift over time) which we all struggle with on a daily basis. Until we, as a diving community, truly accept and understand 'human error', the opportunity to develop a Just Culture is very limited, and without a Just Culture in place, learning from failure is not effective because the focus is on negative outcomes rather than how it made sense to those involved.

Finally, another reason for not dealing with this topic directly, is that I would have opened myself up to specific challenges when criticising specific parts of the industry. To make specific challenges, I would need to have had rock-solid evidence of failures at the organisational and supervisory levels, with a confidence that could be defended in a court of law, and that is missing in many cases. As such, I didn't talk about that even though there are lots of papers written in other industries (which aren't regulated) about how to create change. The key attribute for those organisations who achieved change in safety and performance was that their leadership was focused on making the change and it was commercially viable to do so. In diving, creating wholesale change is expensive and you have to recoup that somehow. The general metric of safety in diving is based around the number of dead divers and law-suits. In the grand scheme of things, there aren't too many of those, fortunately.

Now that I've heard interviews I can't read what you write without it being in a British accent

king_of_battle

Contributor

@GLOC Thank you for the response. Its rare to hear back from an author. I appreciate it. I met you very briefly at Sea Rovers with my wife a few years ago when you gave an overview of your seminar. She is an investigator, also in the biotech industry, trying to determine root causes and corrective actions when things don't go as planned. We had both seen the 'swiss cheese' model countless times but you were the first one we'd seen animate it to demonstrate that failure won't always happen unless everything perfectly aligns.

I agree that regulation isn't the answer - hopefully it didn't seem like I was advocating for that. I don't think we want that or would be prepared for what that looks like.

As you said at the end of your post reassigning 'blame' has been the hardest shift in my industry and continues to be within the dive industry - just looking at several of the A&I threads here is telling. At my company we are still fighting against managers putting metrics around the deviation rate of individuals tying that into performance management/bonuses/raises while knowing we have systems in place that set them up for failure. The single largest obstacle I'm trying to overcome is collecting data to understand both what a baseline for operations are and so we have a more holistic understanding when things go unexpectedly. We have the same challenge in diving.

~~~

To anyone reading this, in his book there is a discussion on divers sending more information about incidents and near misses, no matter how minor, to places like DAN and BSAC so that we can paint a more complete picture of what diving looks like. Ideally it would come from multiple members of the team to give context to the incident. I think there is opportunity for those organizations to spearhead campaigns in that area. Both have credibility and a legacy of enhancing the safety of divers; arguably more so than many of the training agencies who have competing priorities when it pertains to how divers are certified/qualified. DAN/BSAC both solicit for information but the mentality, even when I see DAN representatives 'in the wild', still leans towards the big near misses, not the small ones happening every day. To some degree we have to be the change we want to see in the world but hopefully they can hold our hand along the way. Read the book - be a part of the change.

EDIT - oh one last thing @GLOC - i'm glad the book was over 10 hours. My bias is that a book, especially nonfiction, can rarely go in depth enough on a topic if it's less than 10 hours in length. I look forward to the next one being in the 20-40 hour range!!

I agree that regulation isn't the answer - hopefully it didn't seem like I was advocating for that. I don't think we want that or would be prepared for what that looks like.

As you said at the end of your post reassigning 'blame' has been the hardest shift in my industry and continues to be within the dive industry - just looking at several of the A&I threads here is telling. At my company we are still fighting against managers putting metrics around the deviation rate of individuals tying that into performance management/bonuses/raises while knowing we have systems in place that set them up for failure. The single largest obstacle I'm trying to overcome is collecting data to understand both what a baseline for operations are and so we have a more holistic understanding when things go unexpectedly. We have the same challenge in diving.

~~~

To anyone reading this, in his book there is a discussion on divers sending more information about incidents and near misses, no matter how minor, to places like DAN and BSAC so that we can paint a more complete picture of what diving looks like. Ideally it would come from multiple members of the team to give context to the incident. I think there is opportunity for those organizations to spearhead campaigns in that area. Both have credibility and a legacy of enhancing the safety of divers; arguably more so than many of the training agencies who have competing priorities when it pertains to how divers are certified/qualified. DAN/BSAC both solicit for information but the mentality, even when I see DAN representatives 'in the wild', still leans towards the big near misses, not the small ones happening every day. To some degree we have to be the change we want to see in the world but hopefully they can hold our hand along the way. Read the book - be a part of the change.

EDIT - oh one last thing @GLOC - i'm glad the book was over 10 hours. My bias is that a book, especially nonfiction, can rarely go in depth enough on a topic if it's less than 10 hours in length. I look forward to the next one being in the 20-40 hour range!!

I actually do read it out loud to her. I can only read "If I were a bunny" so many times.Oh. That's so cute.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 464

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 831

- Replies

- 71

- Views

- 31,646

- Replies

- 14

- Views

- 3,736