Historically, as an underwater explorer and worker, man has accepted the mposed equipment limitations with little protest since he realized that even limited work capability was better than none. A look at some of the early efforts reveals that vision received attention prior to the 13th century, utilizing tortoise shell masks of some sort. Then, just afte 1900 came modern diving goggles and the inherent pressure compensation problems. It is interesting that in the year 1865 a single lens mask was made for a compressed air apparatus called the Aerophore, but that this advance had to be rediscovered for free divers about 1930, and even then it took several additional years before the realization that putting the nose inside the mask would permit equilization and reduce squeeze. All in all, face plates have remained virtually unchanged since the 30's and few makor problems have been resolved.

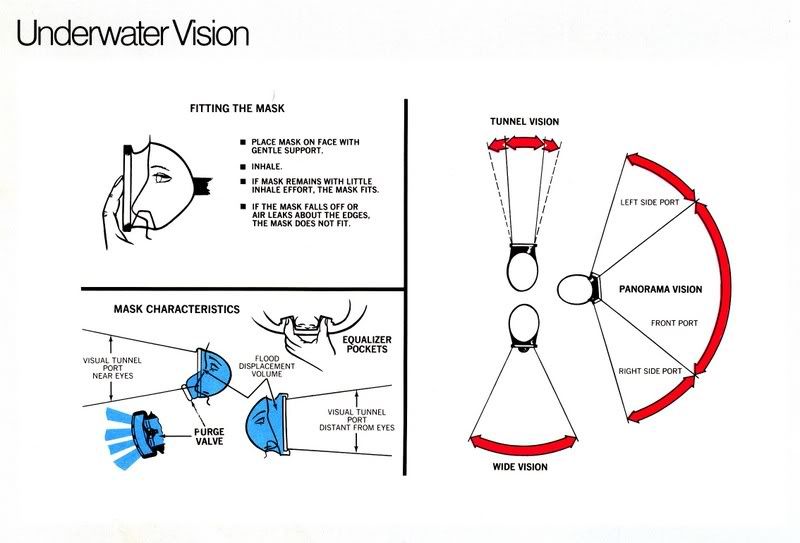

The face plate still provides tunnel vision, magnification, refraction, and in some cases, distortion. The sports diver adapts to these limitations and generally finds little fault with faceplates. However, the increasing demands on working divers should result in a closer look at the problem. An effort to measure the visual fields of representative existing mask configurations was conducted at UCLA. The results are summarized as follows:

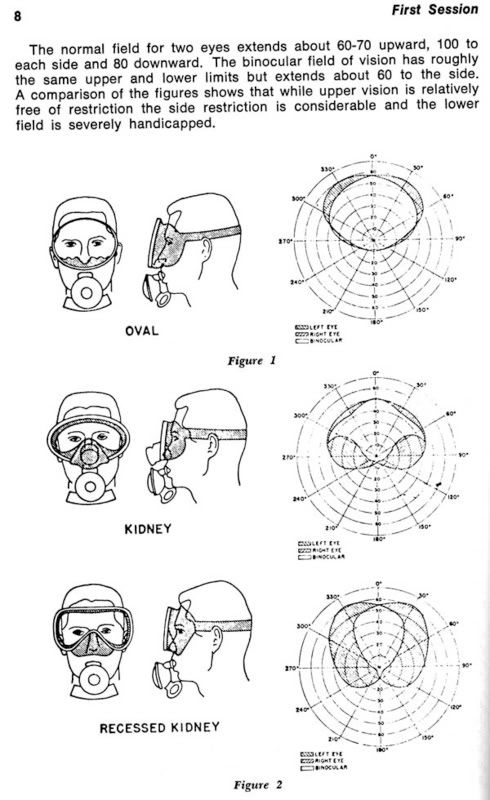

The normal field for two eyes extends about 60-70 upward, 100 to each side, and 80 downward. The binocular field of vision has roughly the same upper and lower limits but extends about 60 to the side. A comparison of the figures shows that wile upper vision is relatively free of restriction the side restriction is considerable and the lower field is severely handicapped...