You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Failed first stage

- Thread starter deepfix

- Start date

Please register or login

Welcome to ScubaBoard, the world's largest scuba diving community. Registration is not required to read the forums, but we encourage you to join. Joining has its benefits and enables you to participate in the discussions.

Benefits of registering include

- Ability to post and comment on topics and discussions.

- A Free photo gallery to share your dive photos with the world.

- You can make this box go away

InTheDrink

Contributor

This is "exactly" why I took my regulators, BCD etc.... all the way to India. I'm not about to risk my life on some companies rental gear. Glad you kept your cool and your wife was close. Well done.

Exactly. BCD failures can be a pain too but your first stage shutting down or a first stage o-ring blowing out isn’t a great place to be.

I’m all for simulations and practice. I used to look like a loony in the pool by myself trying to get myself into all kinds of trouble in a safe environment to see how I would manage and I’d definitely recommend this.

That said, as a newer diver, your 1st stage dying immediately is not ideal.

Apart from extremely rare circumstances I always have redundancy. It’s worth noting that I’m generally a risk taker so if I think redundancy is wise I’d have thought more conservative folk would too.

Additional cost and hassle? Marginal.

Additional safety and psychological safety blanket? Huge

Here's an interesting series of out-takes from the 1950s show, Sea Hunt. The first and last ones star a female diver, probably Zale Perry, who helped teach Lloyd Bridges to dive. The first segment shows her doing a free ascent from probably somewhere around 40 feet of depth. Note how she continues to exhale throughout the ascent, and refuses to buddy breath with "Mike Nelson."

I'll be back a bit later today to address the "CO2 issue," which really is not an issue. I'll explain why.

SeaRat

I'll be back a bit later today to address the "CO2 issue," which really is not an issue. I'll explain why.

SeaRat

InTheDrink

Contributor

Here's an interesting series of out-takes from the 1950s show, Sea Hunt. The first and last ones star a female diver, probably Zale Perry, who helped teach Lloyd Bridges to dive. The first segment shows her doing a free ascent from probably somewhere around 40 feet of depth. Note how she continues to exhale throughout the ascent, and refuses to buddy breath with "Mike Nelson."

I'll be back a bit later today to address the "CO2 issue," which really is not an issue. I'll explain why.

SeaRat

That video is so frigging awesome!!!! Loving the sound track too

Okay, another thought experiment concerning the possibility of building up CO2 in a controlled emergency swimming ascent from 100 feet. CO2 builds up over time when breath-holding.

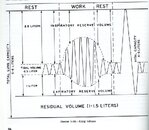

I have done a lot of research on Shallow Water Blackout (SWB), and used it over the years for teaching purposes. I put together the graph below some years ago to explain SWB. You will note that the "Must Breathe" signal occurs somewhere around 50 mm Hg (mercury) in the bloodstream. It under normal circumstances can take a full minute to build up to this lever, where there is an urge to breathe. If a skin diver (snorkeler, breath-hold diver) holds his or her breath that long, they will get a signal to breathe before the oxygen lever in the bloodstream gets down to where a blackout is possible (about 34mm Hg in the bloodstream). If, however, the breath-hold diver does a lot of hyperventilation before the dive, (s)he can "blow off" enough CO2 to postpone that "must breathe" signal to the point where decreasing oxygen levels (which don't trigger this signal) can cause a blackout. (See my graph, below.) This can be compounded by lessening pressure causing the pO2 to decrease in the lungs as the pressure is lessened. This is how deep breath-hold dives can become very dangerous.

I have experienced SWB twice, once is a pool situation and once in open water spearfishing. In the pool situation, it was an underwater swim for distance (I wanted to beat my swim team buddy's record of four lengths of a 20 yard pool). I hyperventilated until I was a bit dizzy, and dove in. I was feeling fine until the last length, and I told myself I would swim to the end of the pool, turn around underwater, take one breast stroke underwater, surface and swim to the side of the pool. This is exactly what I did. The problem is I didn't remember a thing after the pushoff until I was at the side of the pool, breathing deeply. I told our YMCA swim team coach, my friend's mother, what had happened, and she stopped any further underwater swimming contests--forever!

The second time was in Hood Canal, Washington State, when I went down to 40-50 feet, swam around looking for fish to spear with my pole spear, and didn't find any. I started up, and figured I was possibly in trouble so I took off my weight belt and hand-held it (I was wearing 16 pounds of weight). The next thing I remember I was on the surface, still holding onto my weight belt, breathing deeply. My thought was that if I passed out completely, I'd drop my weights and float to the surface where there was a chance of surviving (no buddy). This was in the early 1960s.

So that's SWB; now let's talk about an Controlled Emergency Swimming Ascent (CESA). Here, there is one big difference between a free diver, breath-holding from the surface, and a scuba diver out-of-air at 100 feet. What's that difference? The scuba diver has compressed air, whereas the free diver has his initial surface air, that is compressed, but is at depth probably quite a bit smaller, volume-wise. The breath-hold swimmer, if starting out with 4 liters of air, would have only about 1 liter of air at 100 feet. Also, he would have been adding CO2 it that air from the surface, and reducing oxygen from the surface as he swam down. The scuba diver would have about 2 liters of air, but without reduced oxygen and with no increase of CO2. So with an CESA, the compressed air in the lungs would expand, and the CO2 would be ventilated out as the diver ascended. So the oxygen levels would remain relatively constant during the ascent, as would the CO2. The difference is starting out with compressed air, verses breath-hold compression from the surface. You can also see from the chart I scanned from the U.S. Navy Diving Manual, March 1970, shows a Expiratory Reserve Valume of about 1 liter, plus a Residual Volume of 1-1.5 liters (I underestimated a bit by using 2 liters, when it should be 2-2.5 liters of air in the lungs).

I hope this helps in understanding the physiology of the CESA.

SeaRat

PS, if you want to know more about Zale Perry, please take a look at this link:

Zale Perry - SDI | TDI | ERDI | PFI

PS2, The way we used to do a CESA, we would swim up at the same rate as our bubbles, which if my memory is correct was about 60 feet per minute. In that way, the total ascent would take only about a minute and forty seconds from 100 feet. Now, apparently the recommended rate of ascent is only about 25 feet per minute, which is a much longer time to get to the surface. This is where Stephen got the extremely long time to swim to the surface; I would go the faster way. Realize that there is a lot of safety factors built into the slower rate of ascent, and that for many years we surfaced at a faster rate. We also used the No-Decompression Dive Tables in a manner different from today's diver, using a dive computer. We assumed the entire bottom time (time from surface to the time of ascent), was at the deepest depth. This built into the dive profile a lot of safety, as much of this time was not at the deepest depth, but somewhere above it. Today's diver dives closer to the "knife edge" of the no-decompression tables by using a dive computer than we did using tables. Hence, the 60 feet per minute ascent rate was not extraordinarily fast for purposes of decompression.

I have done a lot of research on Shallow Water Blackout (SWB), and used it over the years for teaching purposes. I put together the graph below some years ago to explain SWB. You will note that the "Must Breathe" signal occurs somewhere around 50 mm Hg (mercury) in the bloodstream. It under normal circumstances can take a full minute to build up to this lever, where there is an urge to breathe. If a skin diver (snorkeler, breath-hold diver) holds his or her breath that long, they will get a signal to breathe before the oxygen lever in the bloodstream gets down to where a blackout is possible (about 34mm Hg in the bloodstream). If, however, the breath-hold diver does a lot of hyperventilation before the dive, (s)he can "blow off" enough CO2 to postpone that "must breathe" signal to the point where decreasing oxygen levels (which don't trigger this signal) can cause a blackout. (See my graph, below.) This can be compounded by lessening pressure causing the pO2 to decrease in the lungs as the pressure is lessened. This is how deep breath-hold dives can become very dangerous.

I have experienced SWB twice, once is a pool situation and once in open water spearfishing. In the pool situation, it was an underwater swim for distance (I wanted to beat my swim team buddy's record of four lengths of a 20 yard pool). I hyperventilated until I was a bit dizzy, and dove in. I was feeling fine until the last length, and I told myself I would swim to the end of the pool, turn around underwater, take one breast stroke underwater, surface and swim to the side of the pool. This is exactly what I did. The problem is I didn't remember a thing after the pushoff until I was at the side of the pool, breathing deeply. I told our YMCA swim team coach, my friend's mother, what had happened, and she stopped any further underwater swimming contests--forever!

The second time was in Hood Canal, Washington State, when I went down to 40-50 feet, swam around looking for fish to spear with my pole spear, and didn't find any. I started up, and figured I was possibly in trouble so I took off my weight belt and hand-held it (I was wearing 16 pounds of weight). The next thing I remember I was on the surface, still holding onto my weight belt, breathing deeply. My thought was that if I passed out completely, I'd drop my weights and float to the surface where there was a chance of surviving (no buddy). This was in the early 1960s.

So that's SWB; now let's talk about an Controlled Emergency Swimming Ascent (CESA). Here, there is one big difference between a free diver, breath-holding from the surface, and a scuba diver out-of-air at 100 feet. What's that difference? The scuba diver has compressed air, whereas the free diver has his initial surface air, that is compressed, but is at depth probably quite a bit smaller, volume-wise. The breath-hold swimmer, if starting out with 4 liters of air, would have only about 1 liter of air at 100 feet. Also, he would have been adding CO2 it that air from the surface, and reducing oxygen from the surface as he swam down. The scuba diver would have about 2 liters of air, but without reduced oxygen and with no increase of CO2. So with an CESA, the compressed air in the lungs would expand, and the CO2 would be ventilated out as the diver ascended. So the oxygen levels would remain relatively constant during the ascent, as would the CO2. The difference is starting out with compressed air, verses breath-hold compression from the surface. You can also see from the chart I scanned from the U.S. Navy Diving Manual, March 1970, shows a Expiratory Reserve Valume of about 1 liter, plus a Residual Volume of 1-1.5 liters (I underestimated a bit by using 2 liters, when it should be 2-2.5 liters of air in the lungs).

I hope this helps in understanding the physiology of the CESA.

SeaRat

PS, if you want to know more about Zale Perry, please take a look at this link:

Zale Perry - SDI | TDI | ERDI | PFI

PS2, The way we used to do a CESA, we would swim up at the same rate as our bubbles, which if my memory is correct was about 60 feet per minute. In that way, the total ascent would take only about a minute and forty seconds from 100 feet. Now, apparently the recommended rate of ascent is only about 25 feet per minute, which is a much longer time to get to the surface. This is where Stephen got the extremely long time to swim to the surface; I would go the faster way. Realize that there is a lot of safety factors built into the slower rate of ascent, and that for many years we surfaced at a faster rate. We also used the No-Decompression Dive Tables in a manner different from today's diver, using a dive computer. We assumed the entire bottom time (time from surface to the time of ascent), was at the deepest depth. This built into the dive profile a lot of safety, as much of this time was not at the deepest depth, but somewhere above it. Today's diver dives closer to the "knife edge" of the no-decompression tables by using a dive computer than we did using tables. Hence, the 60 feet per minute ascent rate was not extraordinarily fast for purposes of decompression.

Attachments

Thanks for the detailed reply @John C. Ratliff

I use to swim a lot, and back then I was able to do one length (50m pool) with one breath. Nowadays, although I swim now and then, I doubt I can do 15 meters. I simply can't overcome my need to breath. Hence my "fear" for CESA situations.

I might try to simulate one though.

Pony (or a buddy) remains my main backup plan.

I use to swim a lot, and back then I was able to do one length (50m pool) with one breath. Nowadays, although I swim now and then, I doubt I can do 15 meters. I simply can't overcome my need to breath. Hence my "fear" for CESA situations.

I might try to simulate one though.

Pony (or a buddy) remains my main backup plan.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 64

- Views

- 8,386

- Replies

- 26

- Views

- 3,237

- Replies

- 28

- Views

- 2,955

- Replies

- 102

- Views

- 9,099

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 3,303