DIVE DRY WITH DR. BILL #883: THE NON-EXPLOSIVE LIMPETS

Back in 1964 Warner Brothers released a film called "The Incredible Mr. Limpet." The main character, played by Don Knotts, transformed into a talking fish that helped the U.S. Navy find and destroy Nazi submarines. I was in high school but had no desire to see the film since, as a budding marine biologist, I knew a limpet was not a fish but a snail!

And in keeping with the theme of sinking enemy ships, back in 1939 a British military man, Major Jefferis, developed limpet mines that could be attached to the hulls of enemy warships. He used powerful magnets to ensure they stayed put beneath the water line before going "KABLOOM."

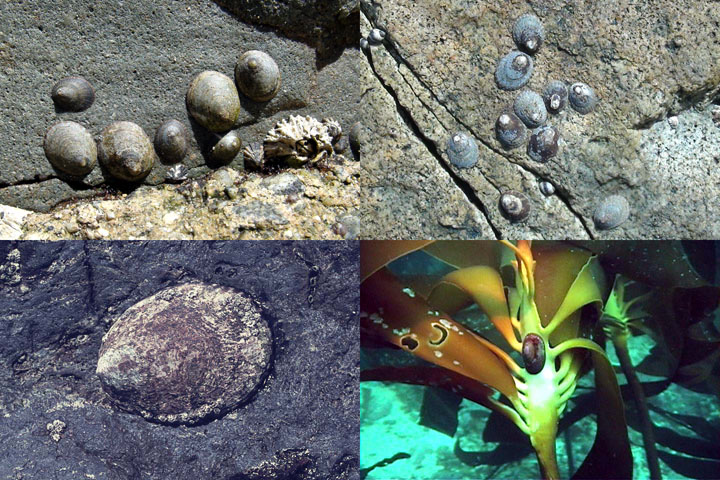

Of course neither of these have much to do with the subject of this column. I'm referring to the snails known as limpets that are often found in the intertidal and subtidal zone. These snails have a somewhat flat, conical shell. They attach to hard substrate on rocky reefs, especially at low tides when some are exposed to the air and warm sunshine. Their strong muscular foot gives them the ability to clamp tightly to the rocks and their conical shells also protect them against heavy wave action. This helps them to stay alive even in the upper tidal zones.

Like other snails, including the beautiful shell-less nudibranchs, they feed using a rasping structure known as a radula. It has many hard "teeth" that can be used to scrape microalgae from the rocky reef when they are submerged. A few even use their radulas to munch on the stipes of brown algae. The radular teeth are an interesting subject (well, at least to us marine biologists!). Since the forward sets of teeth scrape against hard rock, they are constantly being worn down. Rows of new teeth are formed at the rear of the radula and move forward as older teeth disappear.

Most species return to the same spot on the reef as the tide recedes. It is known as the "home scar" Marine biologists believe that the snail finds this spot by retracing its mucous trail which probably contains chemical pheromones.

Limpets are considered tasty fare by seabirds, carnivorous snails like whelks, starfish, fish and others. Back in the 1960s and 1970s when I was teaching marine biology at the Catalina Island School, I used to take my students on "survival hikes" to Little Harbor. My personal dinner at that site was a cactus and limpet stew. I usually chose the larger owl limpets (Lottia gigantea) which were like small abalone. Yum. Little did I know most of my students stopped at the Airport-in-the-Sky for a buffalo burger or steak before reaching camp. Apparently that ruined their appetite when evening arrived... and I thought it was the cookies at the Airport!

And yes, of course my readers want to know the gory details regarding the sex life of these small snails. They are limited in what they can do due to their hard shells. Generally spawning occurs in winter and may be triggered by strong storms which ensure the sperm and eggs get dispersed. The larval forms that develop from the fertilized eggs spend a little time in the plankton seeing the world before settling down.

© 2020 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of nearly 900"Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Limpets clamped down on rocks at low tide; the owl limpet and the kelp limpet dug into kelp.

Back in 1964 Warner Brothers released a film called "The Incredible Mr. Limpet." The main character, played by Don Knotts, transformed into a talking fish that helped the U.S. Navy find and destroy Nazi submarines. I was in high school but had no desire to see the film since, as a budding marine biologist, I knew a limpet was not a fish but a snail!

And in keeping with the theme of sinking enemy ships, back in 1939 a British military man, Major Jefferis, developed limpet mines that could be attached to the hulls of enemy warships. He used powerful magnets to ensure they stayed put beneath the water line before going "KABLOOM."

Of course neither of these have much to do with the subject of this column. I'm referring to the snails known as limpets that are often found in the intertidal and subtidal zone. These snails have a somewhat flat, conical shell. They attach to hard substrate on rocky reefs, especially at low tides when some are exposed to the air and warm sunshine. Their strong muscular foot gives them the ability to clamp tightly to the rocks and their conical shells also protect them against heavy wave action. This helps them to stay alive even in the upper tidal zones.

Like other snails, including the beautiful shell-less nudibranchs, they feed using a rasping structure known as a radula. It has many hard "teeth" that can be used to scrape microalgae from the rocky reef when they are submerged. A few even use their radulas to munch on the stipes of brown algae. The radular teeth are an interesting subject (well, at least to us marine biologists!). Since the forward sets of teeth scrape against hard rock, they are constantly being worn down. Rows of new teeth are formed at the rear of the radula and move forward as older teeth disappear.

Most species return to the same spot on the reef as the tide recedes. It is known as the "home scar" Marine biologists believe that the snail finds this spot by retracing its mucous trail which probably contains chemical pheromones.

Limpets are considered tasty fare by seabirds, carnivorous snails like whelks, starfish, fish and others. Back in the 1960s and 1970s when I was teaching marine biology at the Catalina Island School, I used to take my students on "survival hikes" to Little Harbor. My personal dinner at that site was a cactus and limpet stew. I usually chose the larger owl limpets (Lottia gigantea) which were like small abalone. Yum. Little did I know most of my students stopped at the Airport-in-the-Sky for a buffalo burger or steak before reaching camp. Apparently that ruined their appetite when evening arrived... and I thought it was the cookies at the Airport!

And yes, of course my readers want to know the gory details regarding the sex life of these small snails. They are limited in what they can do due to their hard shells. Generally spawning occurs in winter and may be triggered by strong storms which ensure the sperm and eggs get dispersed. The larval forms that develop from the fertilized eggs spend a little time in the plankton seeing the world before settling down.

© 2020 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of nearly 900"Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Limpets clamped down on rocks at low tide; the owl limpet and the kelp limpet dug into kelp.