DIVE DRY WITH DR. BILL #837: DRIFT AWAY BUT NOT WITH DOBIE GRAY

Back at Harvard some 50+ years ago I had two very important mentors. E. O. Wilson's class on evolution introduced me to island biogeography. At that time he and Robert MacArthur had published a germinal paper on the subject and it intrigued me. My other mentor was H. Barraclough "Barry" Fell who I worked with during my upperclass years and for 7 1/2 years after graduation. He introduced me to kelp rafting (drifting kelp paddies) as a means of explaining dispersal in marine critters.

When I arrived on Catalina in 1969, I was charged with developing a four year science curriculum for my students using the island and the surrounding ocean as our "natural laboratory." My field ecology class was a favorite and it included studying kelp rafts as one mode of dispersal and plankton tows to look both at the permanent plankters as well as the fish and invertebrate larval forms that resided there temporarily as they dispersed and sought a new home far from mom and dad.

Fortunately my meager science department budget allowed me to purchase a real plankton net to conduct the latter studies. I think it cost a whopping $125 back in the early 1970s, more than half my annual budget! It was well worth it as it proved to be a real winner for my students. Watching hundreds of tiny criiters through a Stereozoom microscope, swimming around in a petri dish, brought shouts of wonder.

Many conservation-oriented folks worry about the so-called "lungs of the Earth," the Amazonian rain forest. Yet how many realize that plant plankton (phytoplankton) and coastal algae in the ocean may actually provide up to 70% of the Earth's oxygen? Therefore, it should be extremely important to ensure the health of plankton communities in the ocean. Oh, and photosynthetic organisms in our salt water toilets here on Catalina provide a spectacular display known as the "green flush" at night!

The plant plankton provides food for many small invertebrates in the permanent plankton ecosystem. These include copepods, foraminifera and other small critters. They in turn serve as food for carnivorous plankton as well as many of the fish species of importance to human food chains.

My plankton lab stressed two things: the diversity of life in the plankton community, and the presence of temporary planktonic larvae. The latter was critical in the study of dispersal to isolated locations such as Catalina Island. Eggs fertilized over on the "Big Island" (aka, the mainland) could hatch into larval forms that drifted in the ocean currents until they reached a suitable place to settle out on the island. These temporary plankton are known as meroplankton.

We commonly found larval forms of sea stars, sea urchins, barnacles, crabs, lobster and other invertebrates... not to mention the larval forms of normally bottom-dwelling fish. Any one of these meroplankton could drift over to Catalina or any offshore island and colonize them. I wish I could drift away to Palau or Australia or South America for a few warm water dives!

© 2019 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of over 800 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

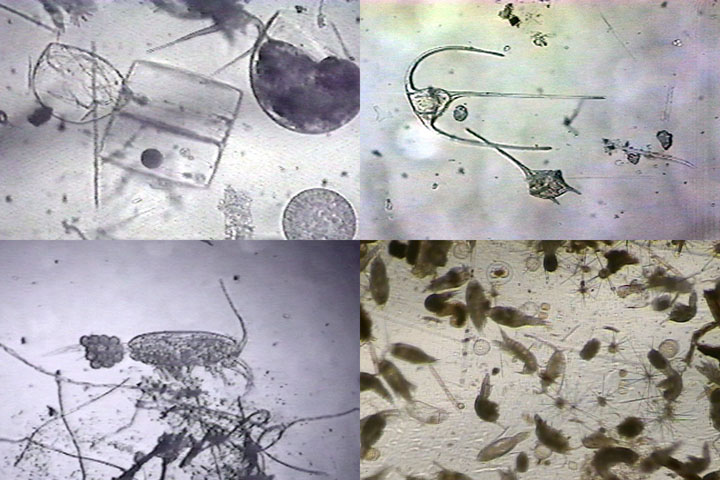

Image caption: Photosynthetic diatom and dinoflagellate produce our oxygen; copepod with eggs and view of plankton sample from Sea of Cortez.

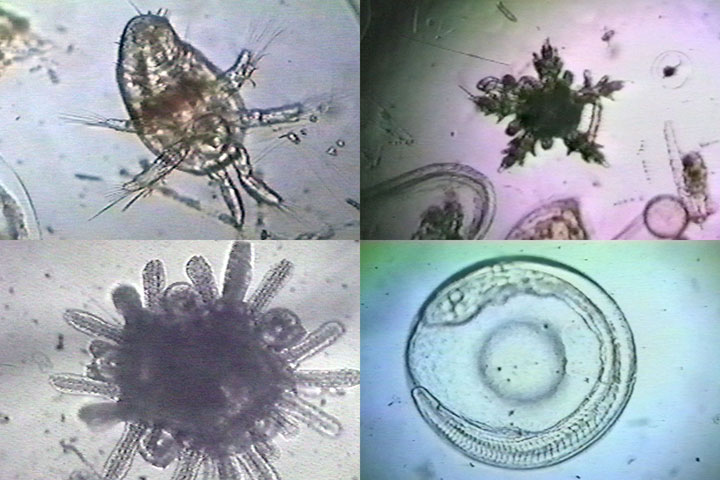

Image caption: Meroplankton: barnacle, starfish, and sea urchin larvae; fish egg with developing larva.

Image caption: "Primitive" plankton net for those on a budget!

Back at Harvard some 50+ years ago I had two very important mentors. E. O. Wilson's class on evolution introduced me to island biogeography. At that time he and Robert MacArthur had published a germinal paper on the subject and it intrigued me. My other mentor was H. Barraclough "Barry" Fell who I worked with during my upperclass years and for 7 1/2 years after graduation. He introduced me to kelp rafting (drifting kelp paddies) as a means of explaining dispersal in marine critters.

When I arrived on Catalina in 1969, I was charged with developing a four year science curriculum for my students using the island and the surrounding ocean as our "natural laboratory." My field ecology class was a favorite and it included studying kelp rafts as one mode of dispersal and plankton tows to look both at the permanent plankters as well as the fish and invertebrate larval forms that resided there temporarily as they dispersed and sought a new home far from mom and dad.

Fortunately my meager science department budget allowed me to purchase a real plankton net to conduct the latter studies. I think it cost a whopping $125 back in the early 1970s, more than half my annual budget! It was well worth it as it proved to be a real winner for my students. Watching hundreds of tiny criiters through a Stereozoom microscope, swimming around in a petri dish, brought shouts of wonder.

Many conservation-oriented folks worry about the so-called "lungs of the Earth," the Amazonian rain forest. Yet how many realize that plant plankton (phytoplankton) and coastal algae in the ocean may actually provide up to 70% of the Earth's oxygen? Therefore, it should be extremely important to ensure the health of plankton communities in the ocean. Oh, and photosynthetic organisms in our salt water toilets here on Catalina provide a spectacular display known as the "green flush" at night!

The plant plankton provides food for many small invertebrates in the permanent plankton ecosystem. These include copepods, foraminifera and other small critters. They in turn serve as food for carnivorous plankton as well as many of the fish species of importance to human food chains.

My plankton lab stressed two things: the diversity of life in the plankton community, and the presence of temporary planktonic larvae. The latter was critical in the study of dispersal to isolated locations such as Catalina Island. Eggs fertilized over on the "Big Island" (aka, the mainland) could hatch into larval forms that drifted in the ocean currents until they reached a suitable place to settle out on the island. These temporary plankton are known as meroplankton.

We commonly found larval forms of sea stars, sea urchins, barnacles, crabs, lobster and other invertebrates... not to mention the larval forms of normally bottom-dwelling fish. Any one of these meroplankton could drift over to Catalina or any offshore island and colonize them. I wish I could drift away to Palau or Australia or South America for a few warm water dives!

© 2019 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of over 800 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Photosynthetic diatom and dinoflagellate produce our oxygen; copepod with eggs and view of plankton sample from Sea of Cortez.

Image caption: Meroplankton: barnacle, starfish, and sea urchin larvae; fish egg with developing larva.

Image caption: "Primitive" plankton net for those on a budget!