DIVE DRY WITH DR. BILL #733: DANGEROUS LIAISONS... NOT!

I've dived in many places around the world with numerous species of sharks, the deadly blue-ring octopus and the toxic puffer fish. However, one of the most dangerous critters I've experienced has been right here in our own dive park. No, I'm not referring to other members of the species Homo sapiens (although at times they qualify). I'm talking about a fairly small colonial critter that frequents our rocky reefs.

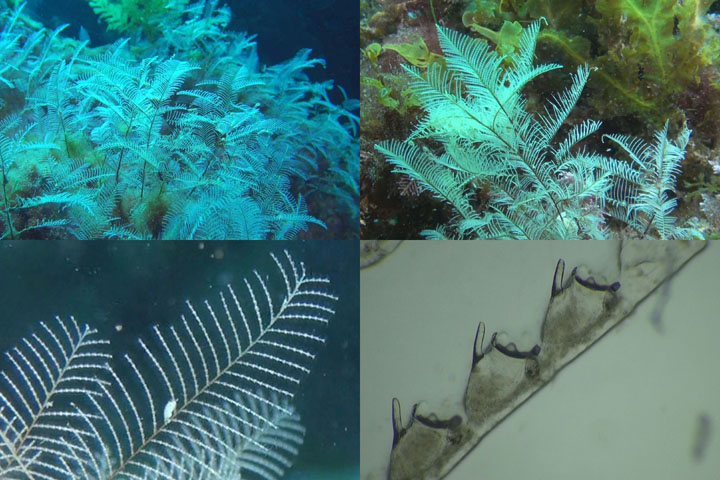

Guessed it yet? I didn't think so. Although it is white in color, it is not great and white. It is small and white. You may totally miss it if you swim over the reef looking for the landlord or even a garibaldi. However, if your bare skin makes contact with it, you will certainly feel its sting! I'm talking about the white feather hydroid (family Plumulariidae).

Back in the days before I started shooting video, I would often dive in a 3mm shortie wetsuit during the warmer months. My abundant bioprene would keep me toasty even over several dives. It also guaranteed that I would return home with red welts on my legs and arms thanks to this tiny relative of the jellyfish. Once I started filimg, the extreme camera shake suggested I was far colder than I tought so I started wearing a full length wetsuit... and the white feather hydroids bothered me no more.

These hydroids actually are a colony of individuals known as polyps. Swimmers and snorkelers are aware of jellyfish which have a large bell from which numerous tentacles hang. They are referred to as medusae. A polyp is the inverse of that with the larger "body" attached to the colony and tentacles that extend outward. Think of their other relatives the sea anemones and coral.

Hydroids are colonies of vicious predators. They lack the sharp teeth of a shark, but use tiny tentacles like that of a miniature jellyfish to capture their planktonic prey. Like sea jellies, these tentacles are full of stinging cells known as nematocysts. For this reason hydroids, sea jellies, siphonophores, corals and sea anemones are grouped in the Phylum Cnidaria (formerly known as Coelenterata). It is these very same nematocysts that sting human flesh... although we are far more than a mouthful for these tiny critters. The sting in this case is their means of defense.

So much for munching. No good Dive Dry column would fail to cover the other "M" word common to all critters, mating (or, more accurately, reproduction since it doesn't always take two to tango... or tangle). Don't worry, Moms and Dads... the sex life of hydroids barely rates a PG rating.

These hydroid colonies are either male or female. They contain miniature male or female medusae that look like tiny jellyfish. The male medusae release sperm which fertilizes the eggs of the female medusae in a nearby colony. From this sacred union, a tiny worm-like larva develops. Unlike some larvae, it does not seek greener pastures by drifting away in the plankton. Instead it crawls away from the parents and begins a new hydroid colony through asexual reproduction. Thus the young colonies are located close to the parents and these hydroids may form dense clusters at times.

So, I hope this column has proven educational for my readers who enter our waters only duriung the warmer months. Beware of the stinging sea jellies and other Cnidarians, but don't overlook the small stuff. If you do, you may end up with itchy red welts on your legs and arms like I used to!

© 2017 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of over 700 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Thick cluster of white feather hydroids and smaller group; close-up of the feather structure and microscopic view of the homes of the individual polyps.

I've dived in many places around the world with numerous species of sharks, the deadly blue-ring octopus and the toxic puffer fish. However, one of the most dangerous critters I've experienced has been right here in our own dive park. No, I'm not referring to other members of the species Homo sapiens (although at times they qualify). I'm talking about a fairly small colonial critter that frequents our rocky reefs.

Guessed it yet? I didn't think so. Although it is white in color, it is not great and white. It is small and white. You may totally miss it if you swim over the reef looking for the landlord or even a garibaldi. However, if your bare skin makes contact with it, you will certainly feel its sting! I'm talking about the white feather hydroid (family Plumulariidae).

Back in the days before I started shooting video, I would often dive in a 3mm shortie wetsuit during the warmer months. My abundant bioprene would keep me toasty even over several dives. It also guaranteed that I would return home with red welts on my legs and arms thanks to this tiny relative of the jellyfish. Once I started filimg, the extreme camera shake suggested I was far colder than I tought so I started wearing a full length wetsuit... and the white feather hydroids bothered me no more.

These hydroids actually are a colony of individuals known as polyps. Swimmers and snorkelers are aware of jellyfish which have a large bell from which numerous tentacles hang. They are referred to as medusae. A polyp is the inverse of that with the larger "body" attached to the colony and tentacles that extend outward. Think of their other relatives the sea anemones and coral.

Hydroids are colonies of vicious predators. They lack the sharp teeth of a shark, but use tiny tentacles like that of a miniature jellyfish to capture their planktonic prey. Like sea jellies, these tentacles are full of stinging cells known as nematocysts. For this reason hydroids, sea jellies, siphonophores, corals and sea anemones are grouped in the Phylum Cnidaria (formerly known as Coelenterata). It is these very same nematocysts that sting human flesh... although we are far more than a mouthful for these tiny critters. The sting in this case is their means of defense.

So much for munching. No good Dive Dry column would fail to cover the other "M" word common to all critters, mating (or, more accurately, reproduction since it doesn't always take two to tango... or tangle). Don't worry, Moms and Dads... the sex life of hydroids barely rates a PG rating.

These hydroid colonies are either male or female. They contain miniature male or female medusae that look like tiny jellyfish. The male medusae release sperm which fertilizes the eggs of the female medusae in a nearby colony. From this sacred union, a tiny worm-like larva develops. Unlike some larvae, it does not seek greener pastures by drifting away in the plankton. Instead it crawls away from the parents and begins a new hydroid colony through asexual reproduction. Thus the young colonies are located close to the parents and these hydroids may form dense clusters at times.

So, I hope this column has proven educational for my readers who enter our waters only duriung the warmer months. Beware of the stinging sea jellies and other Cnidarians, but don't overlook the small stuff. If you do, you may end up with itchy red welts on your legs and arms like I used to!

© 2017 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of over 700 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Thick cluster of white feather hydroids and smaller group; close-up of the feather structure and microscopic view of the homes of the individual polyps.