One of the lessons I learned while researching these threads is that underwater hunting to put food on the table hugely influenced basic equipment design, including snorkels, in the early days. This pursuit would presumably have involved spending long periods afloat on the surface, watching what was going on below, identifying potential prey, making brief forays downwards to approach and catch the quarry. So the earliest snorkels and snorkel-masks were primarily designed for spearfishing in the Med or the Pacific and not for the recreational exploratory breath-hold diving activity that followed during the 1950s.

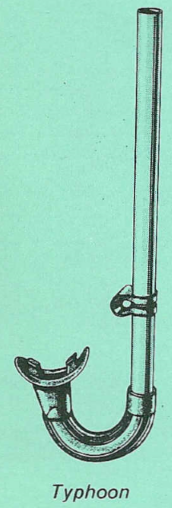

My first snorkel for recreational underwater swimming was a J-shaped device whose alloy barrel was topped with a ball-valve. It served its purpose because from the start I understood what its limitations were as well as its benefits. I no longer have that snorkel, but I was delighted recently to win a similar Typhoon T1 breathing tube on eBay in pristine condition, topped with a splash cap. The alloy barrel made the device almost indestructible, while one of the modern contoured plastic and silicone snorkels I have in my collection shattered into tiny sharp fragments when I accidentally stepped on it a month ago. It has been my own experience that older gear seems relatively simpler, more substantial and hence more durable, which is one of the reasons why I enjoy collecting historical equipment and researching its development against the national backgrounds where it was produced.

Escualo BC (Mexico)

Escualo BC (Mexico)