You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Why not treat DCS yourself?

- Thread starter WetSEAL

- Start date

Please register or login

Welcome to ScubaBoard, the world's largest scuba diving community. Registration is not required to read the forums, but we encourage you to join. Joining has its benefits and enables you to participate in the discussions.

Benefits of registering include

- Ability to post and comment on topics and discussions.

- A Free photo gallery to share your dive photos with the world.

- You can make this box go away

I have finally read through this thread, and would like to contribute a few things. Here's a quote out of the U.S. Navy Diving Manual, Rev. 7:

- 3‐9.3.6 Treating Decompression Sickness. Treatment of decompression sickness is accomplished by recompression. This involves putting the victim back under pressure to reduce the size of the bubbles to cause them to go back into solution and to supply extra oxygen to the hypoxic tissues. Treatment is done in a recompression chamber, but can sometimes be accomplished in the water if a chamber cannot be reached in a reasonable period of time. Recompression in the water is notrecommended, but if undertaken, must be done following specified procedures.Further discussion of the symptoms of decompression sickness and a complete discussion of treatment are presented in Volume 5.

http://www.navsea.navy.mil/Portals/...ING MANUAL_REV7.pdf?ver=2017-01-11-102354-393

Continuing:

In-Water Recompression. Recompression in the water should be considered an option of last resort, to be used only when no recompression facility is on site,symptoms are significant and there is no prospect of reaching a recompressionfacility within a reasonable timeframe (12–24 hours). In an emergency, anuncertified chamber may be used if, in the opinion of a qualified ChamberSupervisor (DSWS Watchstation 305), it is safe to operate. In divers with severe Type II symptoms, or symptoms of arterial gas embolism (e.g., unconsciousness, paralysis, vertigo, respiratory distress (chokes), shock, etc.), the risk of increased harm to the diver from in-water recompression probably outweighs any anticipatedbenefit. Generally, these individuals should not be recompressed in the water, butshould be kept at the surface on 100 percent oxygen, if available, and evacuated to a recompression facility regardless of the delay. The stricken diver should begin breathing 100 percent oxygen immediately (if it is available). Continue breathing oxygen at the surface for 30 minutes before committing to recompress in the water. If symptoms stabilize, improve, or relief on 100 percent oxygen is noted, do not attempt in-water recompression unless symptoms reappear with their original intensity or worsen when oxygen is discontinued. Continue breathing 100 percent oxygen as long as supplies last, up to a maximum time of 12 hours. The patient may be given air breaks as necessary. If surface oxygen proves ineffective after 30 minutes, begin in-water recompression. To avoid hypothermia, it is important to consider water temperature when performing in-water recompression.

In-Water Recompression Using Air. In-water recompression using air is always less preferable than in-water recompression using oxygen.

17-5.4.2.1

n n n

n n n n n

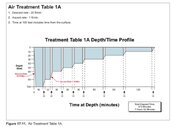

Follow Air Treatment Table 1A as closely as possible.

Use either a full face mask or, preferably, a surface-supplied helmet UBA.

Never recompress a diver in the water using a SCUBA with a mouth pieceunless it is the only breathing source available.

Maintain constant communication.

Keep at least one diver with the patient at all times.

Plan carefully for shifting UBAs or cylinders.

Have an ample number of tenders topside.

If the depth is too shallow for full treatment according to Air Treatment Table 1A:

n Recompress the patient to the maximum available depth.

n Remain at maximum depth for 30 minutes.

n Decompress according to Air Treatment Table 1A. Do not use stops shorter than those of Air Treatment Table 1A.

http://www.navsea.navy.mil/Portals/103/Documents/SUPSALV/Diving/US DIVING MANUAL_REV7.pdf?ver=2017-01-11-102354-393

Attachments

A couple of thoughts:

First, with all this in-water treatment equipment, why bother? Why is procuring an actual recompression chamber for emergency use not even considered now by tech divers? One of the first things Jacques Cousteau did when he equipped the Calypso was to put on it a recompression chamber, and he used it, showing it in his film, The Silent World. Tech divers have enough people, and clubs, and do their own dive expeditions. In the 1950s you could buy a recompression chamber through U.S. Divers Company, according to the book, Dive, the complete book of skin diving, by Rick and Barbara Carrier (page 279). It was collapsible and portable, with a hand pump. So why not equip the boat with a portable recompression chamber? (See these links for ones available now.)

I put this question to Spence Cambell, who pioneered recompression and decompression illness studies using rats and goats, then himself. His reply was that he feels that today's tech divers are not equipping themselves correctly, and that for these kinds of dives, a recompression chamber is necessary, as do I. If you care to read some of his exploits, including his expeditions to the Cobb Sea Mount, pick up his book, After the Swim. Spence equipped their dive ship with a recompression chamber, which was used as their dives were to 200+ feet.

One other thought, and that is that it is sometimes difficult to determine whether a person has DCS or an air embolism. Treatment is much the same, but with air embolism the person is placed into the Trendellenburg position:

Finally, there is a misnomer in that "under pressure" with oxygen is not really reducing the bubbles too much, as the depth is severely restricted with in-water treatment of DCS. At 25-30 feet, there will be some reduction, but it is not the same as the chamber treatments that the U.S. Navy uses, which start on air at 165 feet, and finish on pure oxygen. (Take a look at the U.S. Navy Tables in the above posts.) This does increase the diffusion gradient of the nitrogen out of the bloodstream though, so there is an effect. If the initial bubbles are big, then this will also help.

SeaRat

John C. Ratliff, MSPH-Industrial Hygiene

First, with all this in-water treatment equipment, why bother? Why is procuring an actual recompression chamber for emergency use not even considered now by tech divers? One of the first things Jacques Cousteau did when he equipped the Calypso was to put on it a recompression chamber, and he used it, showing it in his film, The Silent World. Tech divers have enough people, and clubs, and do their own dive expeditions. In the 1950s you could buy a recompression chamber through U.S. Divers Company, according to the book, Dive, the complete book of skin diving, by Rick and Barbara Carrier (page 279). It was collapsible and portable, with a hand pump. So why not equip the boat with a portable recompression chamber? (See these links for ones available now.)

I put this question to Spence Cambell, who pioneered recompression and decompression illness studies using rats and goats, then himself. His reply was that he feels that today's tech divers are not equipping themselves correctly, and that for these kinds of dives, a recompression chamber is necessary, as do I. If you care to read some of his exploits, including his expeditions to the Cobb Sea Mount, pick up his book, After the Swim. Spence equipped their dive ship with a recompression chamber, which was used as their dives were to 200+ feet.

One other thought, and that is that it is sometimes difficult to determine whether a person has DCS or an air embolism. Treatment is much the same, but with air embolism the person is placed into the Trendellenburg position:

This was taught to me years ago when I was a USAF Pararescueman. Obviously, this position is rather impossible with in-water treatment of DCS.In cases of venous air embolism, Durant’s maneuver is performed [18,19], by placing the patient in the left lateral decubitus and Trendelenburg position. This serves to encourage the air bubble to move out of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) and into the right atrium, thereby relieving the “air-lock” effect responsible for potentially catastrophic cardiopulmonary collapse. It is important to note that, in the case of arterial air embolism, patients should be kept in the flat supine position as the head-down position may worsen cerebral edema [20].

Air Embolism: Practical Tips for Prevention and Treatment

Finally, there is a misnomer in that "under pressure" with oxygen is not really reducing the bubbles too much, as the depth is severely restricted with in-water treatment of DCS. At 25-30 feet, there will be some reduction, but it is not the same as the chamber treatments that the U.S. Navy uses, which start on air at 165 feet, and finish on pure oxygen. (Take a look at the U.S. Navy Tables in the above posts.) This does increase the diffusion gradient of the nitrogen out of the bloodstream though, so there is an effect. If the initial bubbles are big, then this will also help.

SeaRat

John C. Ratliff, MSPH-Industrial Hygiene

I don't think that anyone would argue that a chamber nearby would be the perfect solution, however that's never going to happen for many reasons in many places due to costs unfortunately.

Add the cost of properly trained people to operate the chambers, including tenders to accompany the patient.

I'm not sure how accurate this link below is but there isn't a lot of chambers currently available globally.

Worldwide Hyperbaric Chamber Locator, Contact London Recompression & Hyperbaric facilities - The London Diving Chamber

As for my own personal viewpoint of the two available in UAE, none are on the east coast where we do all of our tech diving, and you'd better have good connections to get into the chamber run by the military, or hope that Dr. Barbara is not on holiday otherwise you're screwed!

Looking briefly at other popular dive destinations:

Sipadan, in Sabah, Malaysia, nearest chamber is in Kuala Lumpur on peninsula Malaysia

Philippines, if you're outside of Anilao or Puerto Galera, you're stuffed.

Manado in Sulawesi, Indonesia is fine but diving at Raja Ampat will involve a flight to Manado or Bali.

Bali is covered, might take a while to get there on the narrow roads.

Should liveaboards carry small chambers and trained staff? It would certainly be useful, but how well would they be maintained especially in third world countries where we all like to travel and dive cheaply.

The risks are low, but the best option first is to make sure that you have DAN insurance to start with and have a plan should the sh!t hit the fan before you leave home. I wouldn't expect that many local dive ops to be up to date in SE Asia or even have a plan.

I'm currently in Penang, Malaysia and I was checking out Pulau Weh at the northern tip of Sumatra, Indonesia. The nearest chamber is probably KL in Malaysia, although there is one in Ipoh or it could be in Phuket, Thailand. However either of these options requires a couple of flights.

What is the cost of running and maintaining a chamber with qualified staff 24/7?

Back in the 80s when I worked as a Hyperbaric chamber operator for sat systems I was paid GBP150/ Day for a 12 hour shift, so I suspect that salary has increased over the past 30 years.

On most boats I dive from there is practically insufficient space to get all of our gear on board never mind fit a portable chamber.

Add the cost of properly trained people to operate the chambers, including tenders to accompany the patient.

I'm not sure how accurate this link below is but there isn't a lot of chambers currently available globally.

Worldwide Hyperbaric Chamber Locator, Contact London Recompression & Hyperbaric facilities - The London Diving Chamber

As for my own personal viewpoint of the two available in UAE, none are on the east coast where we do all of our tech diving, and you'd better have good connections to get into the chamber run by the military, or hope that Dr. Barbara is not on holiday otherwise you're screwed!

Looking briefly at other popular dive destinations:

Sipadan, in Sabah, Malaysia, nearest chamber is in Kuala Lumpur on peninsula Malaysia

Philippines, if you're outside of Anilao or Puerto Galera, you're stuffed.

Manado in Sulawesi, Indonesia is fine but diving at Raja Ampat will involve a flight to Manado or Bali.

Bali is covered, might take a while to get there on the narrow roads.

Should liveaboards carry small chambers and trained staff? It would certainly be useful, but how well would they be maintained especially in third world countries where we all like to travel and dive cheaply.

The risks are low, but the best option first is to make sure that you have DAN insurance to start with and have a plan should the sh!t hit the fan before you leave home. I wouldn't expect that many local dive ops to be up to date in SE Asia or even have a plan.

I'm currently in Penang, Malaysia and I was checking out Pulau Weh at the northern tip of Sumatra, Indonesia. The nearest chamber is probably KL in Malaysia, although there is one in Ipoh or it could be in Phuket, Thailand. However either of these options requires a couple of flights.

What is the cost of running and maintaining a chamber with qualified staff 24/7?

Back in the 80s when I worked as a Hyperbaric chamber operator for sat systems I was paid GBP150/ Day for a 12 hour shift, so I suspect that salary has increased over the past 30 years.

On most boats I dive from there is practically insufficient space to get all of our gear on board never mind fit a portable chamber.

Hello,

The review article David and I wrote on this subject has just been published. ...

I am happy to enter into discussion of the ideas / conclusions articulated in the paper, but please read it first.

Simon M

Simon,

Thank you so much for sharing your article! I have read it fully, found it very informative and a very valuable source of information amidst so much controversy and dogma surrounding this issue. I do have a few questions that I'd much appreciate getting your feedback on, which relate back to some of my most long standing open questions on this thread, so it would be great if you could resolve them

Overall, you have concluced that mild Tier 1 symptoms do not justify the risks of IWR, and Tier 2 symptoms may or may not justify the risk of IWR. Specifically, you have identified several risks of IWR, primarily CNS-O2, patient deterioration during IWR, or other complicating special circumstances that make IWR unsuitable (eg, weather, insufficient exposure protection, etc).

Others in this thread have also mentioned patient deterioration as a risk, which confused me because it is known that recompression would immediatley reduce the size of nitrogen bubbles and one would naturally expect this to provide immediate relief of symptoms (a point you noted in your paper as well). You also provide some concrete statistics related to this...In the various studies you've quoted, it seems that in most of them 95-98% of patients treated with O2 IWR have a complete relief of symptoms, and the only examples you mentioned of deteriorating symptoms during IWR were when air was used instead of O2. If there are no documented examples of patient deterioration during O2 IWR, then why is it still considered a serious risk factor?

2) As for CNS-O2, you noted that "the inspired P02 threshold below which seizures never occur irrespective of duration has not been identified but is lower than exposures recommended for IWR." I am not quite sure what this means. I am confused because the IWR procedures you mentioned do have a defined duration, so it seems it is only the risk of seizure at the prescribed P02 and for the prescribed duration (rather than "irrespective of duration") that should be considered. I do see that IWR recommendations grossly exceed the safe single exposure time limits typically recommended for recreational diving, so is that what you mean? (Shearwater and the CNS Oxygen Clock - Shearwater Research).

You said that you "are not aware of any reports of an oxygen toxicity event during IWR", and this presumably includes all of the data you have surveyed. In the data you have surveyed however, you have demonstrated statistically significant benefits of IWR -- for example, you demonstrated that patient outcome prognosis are significantly reduced when recompression is delayed more than 2 hours, and that the median time from surfacing to treatment at a civilian recompression facility was 2 days. The overall remission rates from chamber treatment you quoted were in the 63-83% range, whereas most of the IWR studies had complete remission closer to 95% of the time. In other words, if we look collectively at all the data you have summarized, it seems you have demonstrated that immediate IWR leads to statistically improving health outcomes as opposed to chamber treatment with the usual delays, and yet in this same data there are no documented examples of O2 IWR risks (eg, no documented reduced patient outcomes due to CNS-O2).

Therefore, I'm having a hard time understanding why IWR is not recommended for say type 1 DCI symptoms based on this data. It seems like an unfair bias to use hypothetical cases of CNS-O2 that did not occur in the meta analysis and give those risks arbitrarily higher weight than the observed and measured risks associated with delayed treatment that were demonstrated in the study. Am I simply misinterpreting this data? Do you believe this recommendation is supported by the data directly, or do you just not feel comfortable making a recommendation that contradicts the status quo due to the controversy surrounding it without additional evidence?

2) Is it possible that the risk of CNS-O2 is actually reduced by the high concentration of nitrogen likely to be in a diver conducting IWR...? I personally do not understand the processes of oxygen toxicity enough to know if this makes sense, but I wonder...if a diver is experiencing symptoms of DCI, they must have a high level of nitrogen loading, and perhaps the presence of these nitrogen bubbles gives something for the O2 to bind to which significantly delays the risk of CNS-O2. Perhaps this might explain why your meta analysis data does not document any examples of CNS-O2, despite that conventional safety thresholds for O2 toxicity are grossly exceeded?

3) Another point, which was not discussed in your paper but which I am curious about, is the discussion of milder IWR treatment for milder DCI symptoms. In your paper you have recommended not using IWR to treat mild Type 1 DCI symptoms (presumably because of the risk of CNS-O2), but it seems that some of the IWR procedures with only minor tweaking could be put well under the conventional recreational diving PP02 safety thresholds, thereby eliminating all significant sources of CNS-O2 risk.

For example, you described a "provisional" protocol during the development of USN TT5/6 that suggested terminating treatment early if a complete relief of symptoms is seen within 10 min at 33 fsw. Such guidance would seem to imply that in many cases (such as with minor DCI symptoms), 10 minutes is enough to completely resolve those symptoms. Hence, it seems that a milder treatment of IWR may be a logical cure of mild symptoms of DCI, without risk of CNS-O2.

You noted that the Intl Assoc of Nitrox and Tech Divers recommended IWR at even shallower depth of 25 fsw. 10 minutes at 25 fsw is really not far outside of conventional safe exposure limits, and if one relaxes this just a little bit -- say one breathes 80% O2 at 25 fsw, then this is only about 1.4 PP0 which, according to NOAA Diving Manual, is safe for recreational diving for up to 140 minutes -- plenty of time to at least try out the first provisional test, and see if symptoms resolve after 10-30 minutes, with zero risk of CNS-O2.

Thank you for your time

There's one major step which I haven't seen addressed yet in this thread: diagnosis.

Ask yourself if you're capable of properly diagnosing another diver who is presenting signs and symptoms of DCI.

I have a medical background, I'd be able to check a diver, but before making any suggestions to or decisions for another diver, I would absolutely get DAN on the phone, discuss my findings with a medical doctor and then follow his/her advice. I simply lack the medical knowledge to take full responsibility on my own for an IWR advice. Maybe a chamber is not reachable within 6 hours, but communication is more likely available to consult a hyperbaric doctor.

Also not discussed: communication with an injured diver. Someone who is in pain, will not make the same rational calculated decisions as you right now sitting behind a screen. Communication will be impaired, difficult, or there's even a language barrier (there are other languages besides English). These will make it difficult to get a good overview of all presenting symptoms. And will make your diagnosis even harder.

I do think IWR is beneficial in many cases, if you prepared for it upfront and have the knowledge to care for a patient. Unfortunately some reactions here make it sound like IWR is as easy as going back to the toilet to properly wipe your ass if you missed a spot.

Ask yourself if you're capable of properly diagnosing another diver who is presenting signs and symptoms of DCI.

I have a medical background, I'd be able to check a diver, but before making any suggestions to or decisions for another diver, I would absolutely get DAN on the phone, discuss my findings with a medical doctor and then follow his/her advice. I simply lack the medical knowledge to take full responsibility on my own for an IWR advice. Maybe a chamber is not reachable within 6 hours, but communication is more likely available to consult a hyperbaric doctor.

Also not discussed: communication with an injured diver. Someone who is in pain, will not make the same rational calculated decisions as you right now sitting behind a screen. Communication will be impaired, difficult, or there's even a language barrier (there are other languages besides English). These will make it difficult to get a good overview of all presenting symptoms. And will make your diagnosis even harder.

I do think IWR is beneficial in many cases, if you prepared for it upfront and have the knowledge to care for a patient. Unfortunately some reactions here make it sound like IWR is as easy as going back to the toilet to properly wipe your ass if you missed a spot.

lv2dive

Formerly known as KatePNAtl

Are you aware that Dr Mitchell is one of the preeminent researchers on decompression *in the world*? Some (several) of your assertions/questions do not seem to take his level of knowledge and expertise into account.

Simon,

Thank you so much for sharing your article! I have read it fully, and I do have a few questions that I'd much appreciate getting your feedback on.

Overall, you have concluced that mild Tier 1 symptoms do not justify the risks of IWR, and Tier 2 symptoms may or may not justify the risk of IWR. Specifically, you have identified several risks of IWR, primarily CNS-O2, patient deterioration during IWR, or other complicating special circumstances that make IWR unsuitable (eg, weather, insufficient exposure protection, etc).

As for patient deterioration as a risk, in the various studies you've quoted, it seems that in most of them 95-98% of patients treated with O2 IWR have a complete relief of symptoms, and the only examples you mentioned of deteriorating symptoms during IWR were when air was used instead of O2. Based on this, it doesn't seem like the data you have surveyed supports the notation that patient deterioration during IWR with O2 is really a significant risk factor. Would you say that there is data to support this, or do you cite this more as a hypothetical risk factor? From a basic physics perspective, it would seem that recompression would reduce bubble size hence provide immediate relief, rather than deterioration (which you also noted in your paper)

2) As for CNS-O2, you noted that "the inspired P02 threshold below which seizures never occur irrespective of duration has not been identified but is lower than exposures recommended for IWR." I find this statement a little confusing because IWR procedures do have a defined duration, so it seems it is only the risk of seizure at the prescribed P02 and for the prescribed duration that should be considered. With that said, I do see that IWR recommendations grossly exceed the safe single exposure time limits typically recommended for recreational diving, so I assume that is what you mean (Shearwater and the CNS Oxygen Clock - Shearwater Research).

You said that you "are not aware of any reports of an oxygen toxicity event during IWR", and this presumably includes all of the data you have surveyed. In that same data, however, you have demonstrated statistical benefits of IWR -- for example, you found the median time from surfacing to treatment at a civilian recompression facility was 2 days (?), and often measured in many hours, and you have also demonstrated statistically that longer delay (>2 hr) leads to a reduced prognosis for recovery at very high significance levels, in comparison to prompt IWR treatment.

In other words, if we look collectively at all the data you have summarized, it seems your data has demonstrated a clear statistical benefit of IWR improving health outcomes as opposed to waiting for civilian chamber treatment (improved prognosis due to shortened delay, much higher rates of full recovery than compared to chamber treatments, and no examples of worsened conditions), and yet in this same data there are no documented examples of O2 IWR risks -- eg, no documented reduced patient outcomes due to CNS-O2.

Therefore, I'm having a hard time understanding how your recommendation to avoid IWR for say type 1 DCI symptoms is a data-driven recommendation. It seems like an unfair bias to use hypothetical cases of CNS-O2 that did not occur in the meta analysis and give them arbitrarily higher weight than cases within the meta analysis, especially when the cases in your meta analysis showed general improvement in patient outcomes when using IWR (generally around 95% recovery) compared to conventional delayed treatment (you showed 63-82% of patients having a full recovery after 1 month follow up). Do you believe this recommendation is supported by the data directly, or do you just not feel comfortable making a recommendation that contradicts standard recommendations due to the controversy surrounding it, without additional evidence?

2) Is it possible that the risk of CNS-O2 is actually reduced by the high concentration of nitrogen likely to be in a diver conducting IWR...? In other words, if a diver is experiencing symptoms of DCI, they must have a high level of nitrogen loading, and perhaps the presence of these nitrogen bubbles gives something for the O2 to bind to which significantly delays the risk of CNS-O2. Perhaps this might explain why your meta analysis data does not document any examples of CNS-O2, despite that conventional safety thresholds for O2 toxicity are grossly exceeded? I am honestly curious.

3) Another point, which was not discussed in your paper but which I am curious about, is the discussion of milder IWR treatment for milder DCI symptoms. In your paper you have recommended not using IWR to treat mild Type 1 DCI symptoms because of the risk of CNS-O2, but it seems that some of the IWR procedures with only minor tweaking could be put well under the conventional recreational diving PP02 safety thresholds, thereby eliminating all significant sources of CNS-O2 risk.

For example, you described a "provisional" protocol during the development of USN TT5/6 that suggested terminating treatment early if a complete relief of symptoms is seen within 10 min at 33 fsw, which would imply that in many cases (perhaps a majority) 10 minutes is enough to completely resolve mild symptoms. You also noted that the Intl Assoc of Nitrox and Tech Divers recommended IWR at even shallower depth of 25 fsw. 10 minutes at 25 fsw is really not far outside of conventional safe exposure limits, and if one relaxes this just a little bit -- say one breathes 80% O2 at 25 fsw, then this is only about 1.4 PP0 which, according to NOAA Diving Manual, is safe for recreational diving for up to 140 minutes -- plenty of time to at least try out the first provisional test, and see if symptoms resolve after 10-30 minutes, with zero risk of CNS-O2.

Thank you for your time

Yeah.Are you aware that Dr Mitchell is one of the preeminent researchers on decompression *in the world*? Some (several) of your assertions/questions do not seem to take his level of knowledge and expertise into account.

The OP does not seem to care what others think, especially if they have any experience or credentials,.and his questions are passive-aggressive attempts to discredit anyone who disagrees with him.

- Messages

- 17,327

- Reaction score

- 13,749

- # of dives

- 100 - 199

Similar threads

- Replies

- 43

- Views

- 4,115

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 278

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 485