You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

USAF Pararescue and Scuba Diving

- Thread starter John C. Ratliff

- Start date

Please register or login

Welcome to ScubaBoard, the world's largest scuba diving community. Registration is not required to read the forums, but we encourage you to join. Joining has its benefits and enables you to participate in the discussions.

Benefits of registering include

- Ability to post and comment on topics and discussions.

- A Free photo gallery to share your dive photos with the world.

- You can make this box go away

Just came across this thread while browsing - very interesting history and very informative on the role the PJ's play. It would be interesting to see / compare what the PJ's do with what the Canadian Sartech's do, and the training they have to go through.

Divegoose

Divegoose

I am going to put some of what I've written from my memoirs here, as they pertain to the subject at hand. This one comes from going through the U.S. Navy School for Underwater Swimmers at Key West, Florida in 1967. My friend and buddy throughout the U.S.S. training was a really funny guy named Bob Means. We did everything in the school together, as we buddied up at the beginning and continued throughout the school (three weeks). While this school was grueling, the training we had endured in Parerescue Pre-Conditioning was even greater, so we had some fun with this school. Bob especially had fun three, and pulled a couple of interesting pranks too. Unfortunately, Bob has passed, and just before his death from cancer, he was able to see what I have written here. I hope you enjoy this, and know that Bob Means' spirit endures.

This photo shows Bob Means on our 1000 yard underwater swim off Key West, Florida. We had numerous compass swims, and as I recall one was at night. Here's what I wrote in my memoir about our 1500 yard swim.

Bob got some treatment for his fish spine, and was okay after a little while. Note that as we left the water, we were allowed to take our fins off, but kept close together, and kept both the regulator mouthpiece in our mouth, and our masks down. Putting our mask on our forehead was worth about 25 pushups with our tanks on. There would be no "Mike Nelson" mask on forehead at the U.S. Naval School for Underwater Swimmers. To this day, some 50 years later, when I exit the water I keep my mask on until I'm completely out (though I have made a few "publicity photos" with my mask up).

SeaRat

I hope you enjoyed that little bit of writing. Bob was a really special guy, and my regret is that although we did communicate in writing, I was not able to see him again before he passed. He had different assignments from me, and after training, we never got together again....In the second week we were introduced to scuba, which stands for self-contained underwater breathing apparatus*. We used the older-style double hose regulators, which convert the tank's high pressure air to the air pressure of the surrounding water/air, and give it on demand. The right hose was for inhalation, the left for exhalation, and the exhaled air exited into the water at exactly the same spot as the diaphragm which controlled the inhaled air. Captain Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Emile Gagnan had patented this process in the 1940's, just after WWII, and the regulator we used was only a second generation design away from the one he originally marketed.

We learned how to disassemble, clean, repair, reassemble, and test the scuba gear. We knew it backwards, and forwards, inside out. Interestingly, some of the regulators had black housings, and the interior parts were platted with gold rather than chrome-plated steel. The reason was so that they were anti-magnetic. The Navy used them for mine-clearing activities, and I believe more than a few were ultimately stolen.

The instructors also took us to the pool for training, where we learned how to clear the breathing tubes, how to take off and put on the equipment underwater, and how to swim underwater an compass course.

During the pool work, we would be harassed. The instructors would swim up to us and pull a face mask off, or turn off our air. We would have to work with out buddy to solve our problems. If we surfaced, we'd be told to get out of the water and do twenty-five pushups. But we couldn't take off our gear. So we did the pushups with twin-tank aqua-lungs on our backs, weighing about 80 pounds.

At times, if this wasn't good enough for us, the whole class would be made to put their mask on underwater, so that it was full of water. We then had to get out of the water, lay down on our backs, and sings songs while doing a flutter kick.

I would have like to have had a recording of those songs. We sang, but all that came out was the sound of drowning men as the water from our masks trickled down the back of our nose and into our throats. We sounded like a group-gargling experiment.

Robert Means became my diving buddy, and was in this position, as the instructor stood close to his feet and barked orders for more flutter kicks and singing. We wore diving booties, made of compressed rubber to keep the fins from chafing our feet and the coral from cutting our soles. These booties had a loose top, which collected water. Means' feet were next to the instructor's leg, and the instructor was wearing leather boots which were loosely tied around his ankles, and cotton stockings. I watched from beside Means as he lifted his leg, as ordered, and deftly poured the cup full of water from his right bootie into the instructor's right boot as he began his flutter kicks. The instructor jumped back, barked "Means, attention!" and Means got up for his ass-chewing, then dropped for twenty-five pushups. We then began our flutter kicks again, with the instructor having sloshed to a safe distance.

The compass courses were open water swims. At first, they were minimum equipment, meaning a life vest, mask and fins with booties. Our fins were Navy issue ones with a blade about a foot long and stiffening ribs. They were of a open heel design, which allowed us to carry them easily, but the heel strap was solid rubber, without any type of adjustment. The blade was as stiff as plywood, so these fins were hard to push through water. But they did give us good acceleration when we needed it.

The two things that the U.S. Navy instructors at the Underwater Swimmers School in Key West impressed upon us was the buddy system and the masks on the forehead. "Who do you think you are, Mike Nelson?" they'd yell if they saw a mask on the forehead. The idea was that the mask on the forehead is in an ideal position to be washed off by a wave.

*We were using U.S. Divers Company's DA Aquamaster regulators, and some were the anti-magnetic versions.

From my unpublished manuscript, Between Air and Water, the Memoir of an USAF Pararescueman," Copyright John C. Ratliff, 2017.

This photo shows Bob Means on our 1000 yard underwater swim off Key West, Florida. We had numerous compass swims, and as I recall one was at night. Here's what I wrote in my memoir about our 1500 yard swim.

...

The fifteen hundred yard swim began like the others, with us being dumped into the ocean off small amphibious boats. We stayed on the surface for a minute, getting our compass bearings. We used a liquid-filled wrist compass with a rotating bazel. In order to sight it in, I needed to hold my left arm straight out in front of me, pointed at the target (a white stand on the distant beach). I then placed my left hand on my right elbow, gripping the elbow, and looking at the compass needle. The needle needed to be lined up on the bezel, so after noting its position when I sighted the target, I adjusted the bezel so that the two directional slashes on the rotating face aligned with the needle inside. This allowed us to keep the same orientation as we swam. After a couple of small adjustments, Robert and I submerged. He stayed off to my right side, handling a rope buddy line between the two of us and the orange buoy on a surface line which marked out position for the instructors, while I swam as I sighted the compass.

We were allowed to surface at the 1000 yard mark and at the 500 yard mark, which we did. I was relieved when I saw the anchor line for the buoys. As we got closer, the water warmed a bit and got cloudier. We started out with 30 foot visibility, then by the 550 yard marker, underwater visibility was down to ten feet or so. The water was warm, and about 80 degrees, so cold wasn't a problem. We continued swimming closer to shore, using my compass sighting, until the visibility got very bad. The visibility was so bad that Bob, with his hands in front of him, bumped into a fish and got a spine in his finger for his efforts. But we remained underwater, sighting the compass and believing in it, until the water was so shallow that our heads broke surface. We were only five feet away from the shore's coral outcropping, and there was the instructor's legs, and the white tower right behind him.

We had hit the beach dead-on and surfaced at our instructor's feet. He was pleased, and told us to walk out, and sit down to wait for the rest of the class. We were first in to the beach too. The warm sun was refreshing, because even in 80 degree water a person chills after awhile.

After several minutes, another buddy team made it to shore, but not quite where they wanted to be. They were twenty or so yards down the beach. Another team came in, then another, until almost all were in. One team had to be pulled from the water as they had turned the wrong direction and were swimming toward Cuba, some 90 miles away. Robert and I enjoyed having accomplished a great swim...

From my unpublished manuscript, Between Air and Water, the Memoir of an USAF Pararescueman," Copyright John C. Ratliff, 2017.

Bob got some treatment for his fish spine, and was okay after a little while. Note that as we left the water, we were allowed to take our fins off, but kept close together, and kept both the regulator mouthpiece in our mouth, and our masks down. Putting our mask on our forehead was worth about 25 pushups with our tanks on. There would be no "Mike Nelson" mask on forehead at the U.S. Naval School for Underwater Swimmers. To this day, some 50 years later, when I exit the water I keep my mask on until I'm completely out (though I have made a few "publicity photos" with my mask up).

SeaRat

Last edited:

73diver

Contributor

Very nice thread. Thank you for your service. My best friend from high school and college was a USAF Pararescueman 1968-1972. He spent most of his time at Anderson AFB, Guam. I wound up being a USAF pilot 1969-1976. I never needed the services of the PJ's but was very glad they were there. As you know, a PJ never buys a drink if there is a pilot in the bar.

73diver,

Could you PM his name to me? I'd be interested in knowing who he is, as that is the time frame I was in the regular USAF as a PJ.

John (SeaRat)

Could you PM his name to me? I'd be interested in knowing who he is, as that is the time frame I was in the regular USAF as a PJ.

John (SeaRat)

73diver

Contributor

Wi

Will do.73diver,

Could you PM his name to me? I'd be interested in knowing who he is, as that is the time frame I was in the regular USAF as a PJ.

John (SeaRat)

I have posted some information over on the Vintage Scuba Supply's website that should also be here.

SeaRat

It took the U.S. Coast Guard a long time to come around to the need for rescue swimmers. I had been deployed on a mission in 1969. Here is a letter home, part of my chapter about this recovery:This entry is about my favorite mask, the Scubapro Supervision three-window mask. I have used this mask since the 1970s, and under helicopter rotorwash when training with the 304th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron out of the Portland Air Base, Oregon. We trained in the Columbia River, and I wanted a mask that allowed peripheral vision but yet protected me from the rotor wash spray. I have now worn out four of these masks.

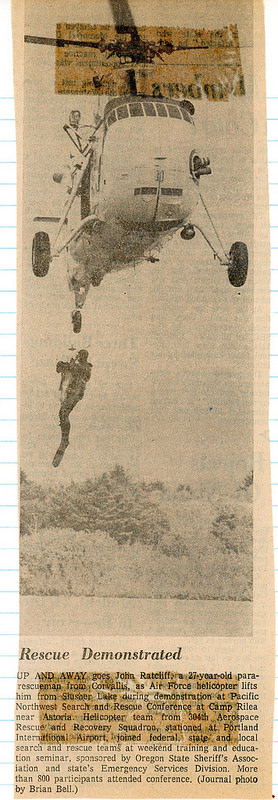

This is an article from the Oregon Journal about our 304th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron training at Camp Rilea, near Astoria, Oregon in 1972. I'm on the hoist, being picked up as a demonstration to the Northwest Search and Rescue Conference. Of note, this was before the U.S. Coast Guard had any Rescue Swimmers, and helped demonstrate the capabilities of Pararescuemen in the water. But it was not until there was a [a href="[URL='http://www.alaska.net/~jcassidy/prinsendam.htm']THE PRINSENDAM FIRE[/URL]"]ship sinking, the M/V Prisendam[/a], and the Coast Guard could not respond in the water, but USAF Pararesuce did, that the Coast Guard decided to start their Rescue Swimmer program. [a href="[URL='http://www.alaska.net/~jcassidy/prinsendam.htm']THE PRINSENDAM FIRE[/URL]"]John Cassidy writes about this rescue here[/a].

I last took this mask to Hawai'i a few weeks back, and for the black neoprene mask, this turned out to be its last swim/dive. When I got back, I decided that it was time for a change, as the mask was actually leaking through one of the supports for the windows. I had taken the mask into the pool last fall when testing my Mares MR-12 II regulator, and got a video of it. Here's a photo from that video:

http://vintagescuba.proboards.com/thread/4699/scuba-snorkeling-masks-snorkels?page=3&scrollTo=39956

I include this mission because it shows our capabilities in 1969. The U.S. Coast Guard did not establish its Rescue Swimmer program until much later, 1984 actually. Below is the letter I received from the Republic of Korea Air Force, and a photo of me receiving the award from Brig. General Rim Soon-Hyuk, along with Major Kekuna, our pilot on the mission.March 17, 1969

Dear Mom, Dad, Skip, Bill & Ken:

In my last letter, I told of our water training that we conducted a week ago last Thursday. Thursday last, on a mission we would rather wouldn't happen, we tested our procedures and found them very effective. It was stormy on the 13th of March when we received the scramble call. A T-33 jet flying from Kwanju had called into Kwanju with engine troubles. We scrambled with the fire suppression kit and orbited near the runway. A storm just off the end of the runway put visibility down to zero, with some icing. The ROKAF T-33 never landed, and Kunsan AB was unable to establish radar or radio contact. We landed, I got my skin diving gear, then went out for a search. After 15 minutes we found the victim’s life raft and helmets. No sign of life was observed. We landed in a mud flat, where the pilots and flight engineer (FE) put on exposure suits and I put on diving equipment. Then we went out for the recovery. The rest is in the rough draft statement I wrote for the ROKAF Accident Investigation Board.

___________________

1625/JCR, Mission # Det 3, 41st ARRWg 007, March 13, 1969

I had very little visual contact with the victims or their equipment before my deployment into the water because I was busy putting on my diving equipment. I was in the door about 10 seconds before TSgt Maxwell tapped me out of the helicopter. The helicopter was in about a 15 foot hoover when I jumped. After entering the water, I swam to the victim and tried to lift him to the water's surface. He was too heavy. Underwater visibility was about six (6) inches. It was hard to determine which part of the victim (arm or leg) I was holding. It was his arm. I found one of his Capewell quick releases for his parachute, which was deployed in the water, and released it. Then I turned him over to get to the other release, and released it also. I tried to blow up his LPU,1 but couldn't find them. The victim's face was bloody and he didn't have a helmet on. After releasing the parachute, I swam him away from his life raft and parachute. I had to cut parachute suspension lines which were tangled around his feet and my swim fins and the tether to his life raft. I signaled for a helicopter pickup of the first victim. The HH-43 helicopter lowered a rescue seat to me, which I disconnected, and hooked the hoist's hook to the victim's parachute harness.

After the first victim was aboard the helicopter, I looked around for the other victim. I saw a helmet, swam to it towing the rescue seat, but the victim wasn't there. I strapped the helmet to the seat. The second helicopter guided me to the second victim.

I swam to the second victim, swimming around his parachute to keep from getting tangled in the lines. I found some suspension lines beside the victim and cut them. I then cut the risers (on the victim's right side, I believe), disconnected the Capewell quick release from the parachute risers on the other side, and checked to see if the victim was tangled in lines. He was not tangled. I also tried to locate his LPU to blow them up, but again couldn't find them. Then I signaled for a second hoist pickup, which was accomplished the same manner as the first.

When the second victim was aboard, I swam to the rescue seat, strapped myself into it, and I was picked up.

Headquarters

Republic of Korea Air Force

Seoul, Korea

1 LPU--Life Preserver, Underarm

SeaRat

Attachments

Last edited:

TONY CHANEY

Contributor

I just spent hours reading everything and enjoyed it deeply. When it comes up in discussion about the elite, I always have to tell others about PJs and I am surprised that therte are so many that does not even know that there are PJs. I once and only brush with a PJ was 02-17/18-2003 in Okinawa, Ikei Island. Japan. We, as a unit, lost one of our Marines when he and two others entered into a water filled sea cave, Two came out on one didn't. From my buddy who was the course director, he said that of all different military branches on the island only the PJs are qualified for this recovery. So I salute you John and all that came before and after your service. I really like the manner in which you write John. Very humble.

So the questions: 1) When jumping with fins on is it hard to keep your feet from blowing up? 2) How did Banger get his nickname? 3) What was your nickname? 4) What was your personal worse case, oh crap moment?

So the questions: 1) When jumping with fins on is it hard to keep your feet from blowing up? 2) How did Banger get his nickname? 3) What was your nickname? 4) What was your personal worse case, oh crap moment?

This has been a great thread. I thought I'd pass this along in tribute to @John C. Ratliff and my son, who, like John, is an Air Force Rescue PJ and a current member of the 304th Rescue Squadron and pictured below.

NASA just published this yesterday:

Pararescue specialists from the 304th Rescue Squadron, located in Portland, Oregon and supporting the 45th Operations Group’s Detachment 3, based out of Patrick Air Force Base, deploy their parachutes and prepare to touch down on the Atlantic Ocean surface during an astronaut rescue training exercise in April.

As the name Guardian Angels suggests, these rescuers are trained to protect. “Most people don’t even know who we are, but we specialize in problem solving in very dynamic environments,” said Brandon Daugherty, space medical contingency specialist with the 45th Operations Group’s Detachment 3. “There are only about 500 pararescue specialists worldwide. We are fully qualified paramedics, and able to perform field surgery, if necessary.” While NASA's strategy for CCP is to have the commercial partners to provide end-to-end crew transportation services, it was determined to be more effective and efficient to rely on the DOD for contingency rescue because of their unique capabilities.

Pararecue specialists have evolved their military capabilities to help commercial partners and NASA. “We’re the only force equipped to do global, worldwide rescue and recovery in any climate. Whether it’s the top of a mountain or the bottom of the ocean, we can get there,” said Daugherty.

https://www.nasa.gov/feature/rescue-operations-take-shape-for-commercial-crew-program-astronauts

NASA just published this yesterday:

Pararescue specialists from the 304th Rescue Squadron, located in Portland, Oregon and supporting the 45th Operations Group’s Detachment 3, based out of Patrick Air Force Base, deploy their parachutes and prepare to touch down on the Atlantic Ocean surface during an astronaut rescue training exercise in April.

As the name Guardian Angels suggests, these rescuers are trained to protect. “Most people don’t even know who we are, but we specialize in problem solving in very dynamic environments,” said Brandon Daugherty, space medical contingency specialist with the 45th Operations Group’s Detachment 3. “There are only about 500 pararescue specialists worldwide. We are fully qualified paramedics, and able to perform field surgery, if necessary.” While NASA's strategy for CCP is to have the commercial partners to provide end-to-end crew transportation services, it was determined to be more effective and efficient to rely on the DOD for contingency rescue because of their unique capabilities.

Pararecue specialists have evolved their military capabilities to help commercial partners and NASA. “We’re the only force equipped to do global, worldwide rescue and recovery in any climate. Whether it’s the top of a mountain or the bottom of the ocean, we can get there,” said Daugherty.

https://www.nasa.gov/feature/rescue-operations-take-shape-for-commercial-crew-program-astronauts

What a fabulous thread John. Thank you for putting all the effort into it.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 514

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 597

- Replies

- 60

- Views

- 4,505

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 579

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 442