GLOC_The Human Diver

Contributor

I agree with Parker Turner's situation. A rarity.

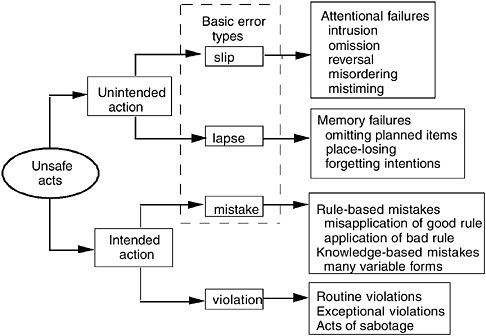

If we classify everything as 'human error' how does that help us resolve the situation?

A: Looking at this case. Destructive goal pursuit (totally focussed on the goals, despite everything else saying stop). Self (over)-confidence. Group-think - supporters didn't want to not support. Lack of assertion within the team to say 'stop' this is madness. Lack of awareness of what might have gone wrong and plan accordingly. Assumption that everything would go to plan.

B: Running out of gas is an outcome, not a cause. Why did they run out of gas? Poor awareness that tank wasn't full to start with. Task fixated so didn't notice consumption. Didn't notice equipment leak. Freeflow and couldn't shutdown. Teamwork didn't help resolve the situation. The checklist study from DAN showed that less than 7% of divers used a checklist prior to a dive. That doesn't sound like an individual problem, that sounds like a system problem!!

Incompetent and unaware can only be corrected through reflective debriefs and that is what D-K showed. If you were are of your own limitations, then you can start to correct them. How much of the 'modern' recreational training is about reflective personal development compared to 'monkey see, monkey do' training? To develop thinking divers we need to create those who learn through 'second-loop learning' understanding 'why' something is done a certain way, not just doing something by rote and because the instructor said do this because you need to complete this task to pass the course.

So back to your point

a) failed to avoid putting yourself in a situation that you were not prepared to handle adequately (avoid)

or

b) you failed to correctly handle a situation you *thought* you were prepared for (cure)

A: How do you know what you are prepared to deal with before the event? If they knew this, they wouldn't likely do that. What about peer pressure to not thumb a dive, hoping it would be okay? The ability to thumb a dive at any time for any reason is based on personal confidence and experience. I have worked on Oil rigs where the crews are given a 'Stop Work Authority' card which is signed by the CEO and they can hold up and say 'Stop'. How often does it get played? Hardly ever because people are afraid of doing so. And that is where the consequences can be very large!! Giving people the tools is fine, but they need to be able to operate them in the social environment they are in.

B: Again, if you thought you were prepared, you thought you were prepared, so you thought it would be ok. Only in hindsight do we see that it wasn't right...

As I have posted elsewhere, Dunning-Kruger also impacts those in the top quartile of a performance group - instead of overestimating their own capabilities, they make assumptions about what those at the bottom quartile should know and do...

It is not an easy problem to solve...especially when the concept of 'safety' and 'risk' are very much at a personal level.

If we classify everything as 'human error' how does that help us resolve the situation?

A: Looking at this case. Destructive goal pursuit (totally focussed on the goals, despite everything else saying stop). Self (over)-confidence. Group-think - supporters didn't want to not support. Lack of assertion within the team to say 'stop' this is madness. Lack of awareness of what might have gone wrong and plan accordingly. Assumption that everything would go to plan.

B: Running out of gas is an outcome, not a cause. Why did they run out of gas? Poor awareness that tank wasn't full to start with. Task fixated so didn't notice consumption. Didn't notice equipment leak. Freeflow and couldn't shutdown. Teamwork didn't help resolve the situation. The checklist study from DAN showed that less than 7% of divers used a checklist prior to a dive. That doesn't sound like an individual problem, that sounds like a system problem!!

Incompetent and unaware can only be corrected through reflective debriefs and that is what D-K showed. If you were are of your own limitations, then you can start to correct them. How much of the 'modern' recreational training is about reflective personal development compared to 'monkey see, monkey do' training? To develop thinking divers we need to create those who learn through 'second-loop learning' understanding 'why' something is done a certain way, not just doing something by rote and because the instructor said do this because you need to complete this task to pass the course.

So back to your point

a) failed to avoid putting yourself in a situation that you were not prepared to handle adequately (avoid)

or

b) you failed to correctly handle a situation you *thought* you were prepared for (cure)

A: How do you know what you are prepared to deal with before the event? If they knew this, they wouldn't likely do that. What about peer pressure to not thumb a dive, hoping it would be okay? The ability to thumb a dive at any time for any reason is based on personal confidence and experience. I have worked on Oil rigs where the crews are given a 'Stop Work Authority' card which is signed by the CEO and they can hold up and say 'Stop'. How often does it get played? Hardly ever because people are afraid of doing so. And that is where the consequences can be very large!! Giving people the tools is fine, but they need to be able to operate them in the social environment they are in.

B: Again, if you thought you were prepared, you thought you were prepared, so you thought it would be ok. Only in hindsight do we see that it wasn't right...

As I have posted elsewhere, Dunning-Kruger also impacts those in the top quartile of a performance group - instead of overestimating their own capabilities, they make assumptions about what those at the bottom quartile should know and do...

It is not an easy problem to solve...especially when the concept of 'safety' and 'risk' are very much at a personal level.