I'll differ with my good friend @couv , sortof, regarding the monkey motion of a more complex adjustment knob.

The single critical deficiency of the G250 is the absence of independent poppet spring tension adjustment. What this means is that lever height is controlled by the orifice position, at the same time as spring tension is changed when you raise or lower the lever. This is why tools such as the "lever bender" were designed: to make up for the lack of an independent lever height adjustment. That's especially critical with the flat diaphragm that the G250 uses.

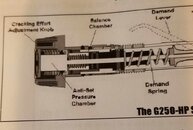

It's why the S600 series is such a wild success. You position the lever with the orifice, and then lower spring tension as much as desired for cracking effort with the small screw inside the adjustment knob. The knob design for the G250 HP was clumsy, as @couv suggests. And the new plastic orifice didn't start well. However, the addition of the ability to lower spring tension was an important addition which presaged all of the developments that followed in the G500, S550, S555 and S600/620 and G260 series regulators. And the plastic orifice has improved to be a reliable standard in the S-series (though I still prefer the metal orifice). One thing the plastic orifice is superior at: shedding ice crystals.

Unfortunately, creating a sealed chamber inside the knob meant that you indeed need a special tool or repeated trial and error to change spring tension on the fly in the G250HP and the 1st iteration G500.

You want the best "G250" in the world? Find a first-generation G500 (with an all metal barrel) and replace the knob assembly with the one from the second generation. That is a G250 as it should have been (now called a G260 with its extra metal bling, and price to match).

Tuning a G260 is like four times as fast as a G250, unless you already set the lever height on that old one before, or you got lucky.

The single critical deficiency of the G250 is the absence of independent poppet spring tension adjustment. What this means is that lever height is controlled by the orifice position, at the same time as spring tension is changed when you raise or lower the lever. This is why tools such as the "lever bender" were designed: to make up for the lack of an independent lever height adjustment. That's especially critical with the flat diaphragm that the G250 uses.

It's why the S600 series is such a wild success. You position the lever with the orifice, and then lower spring tension as much as desired for cracking effort with the small screw inside the adjustment knob. The knob design for the G250 HP was clumsy, as @couv suggests. And the new plastic orifice didn't start well. However, the addition of the ability to lower spring tension was an important addition which presaged all of the developments that followed in the G500, S550, S555 and S600/620 and G260 series regulators. And the plastic orifice has improved to be a reliable standard in the S-series (though I still prefer the metal orifice). One thing the plastic orifice is superior at: shedding ice crystals.

Unfortunately, creating a sealed chamber inside the knob meant that you indeed need a special tool or repeated trial and error to change spring tension on the fly in the G250HP and the 1st iteration G500.

You want the best "G250" in the world? Find a first-generation G500 (with an all metal barrel) and replace the knob assembly with the one from the second generation. That is a G250 as it should have been (now called a G260 with its extra metal bling, and price to match).

Tuning a G260 is like four times as fast as a G250, unless you already set the lever height on that old one before, or you got lucky.