DIVE DRY WITH DR. BILL #748: THE STARS RETURN

This column will not be about the return of Hollywood stars to the former Hotel St. Catherine (Catalina Island) like in the pre-War heyday. And despite the national interest in the recent total eclipse of the sun, I won't be writing about the heavenly bodies like Betelgeuse and Sirius. I've got another group of stars in mind today.

Those of my readers with good memories may think back to a column I wrote about the disastrous disappearance of most sea stars in waters ranging from the Pacific NW to SoCal. First noted way up north, it affected some 40 species of starfish (or sea stars for the PC crowd). The disease has been linked to a densovirus, and this is not the first time it has impacted sea stars and other echinoderms on the West Coast. It is often linked to unusually warm waters such as El Niños and the unusual Blobs that developed a few years ago.

The loss of these significant predators caused further imbalances in the ecology of waters so affected. Sea stars often prey on their cousins the sea urchins and help keep those populations in check. The waters up north were unusually warm, stressing populations of various kelp species. With the added threat of increased urchin numbers, this became a one-two punch for the kelp.

Down south in our local waters, several species of sea stars either disappeared or were present in noticeably lower numbers. Fortunately here in SoCal there are other predators like sheephead to control the populations of urchins. Many of the red and purple urchins also died off here as the warm water accelerates the impact of the same densovirus on them.

As an amateur astronomer, I love that the often dark skies of the island allow us to see many more stars than in downtown "Lost" Angeles. I also love that I can see stars underwater as well. After all, my mentor at Harvard (H. Barraclough Fell) was an echinoderm specialist. Over the last half century, I have experienced other warm water periods (mainly El Niños) when sea stars and sea urchins have largely disappeared. Fortunately they eventually return thanks to larvae that make it out to the island with the plankton and currents.

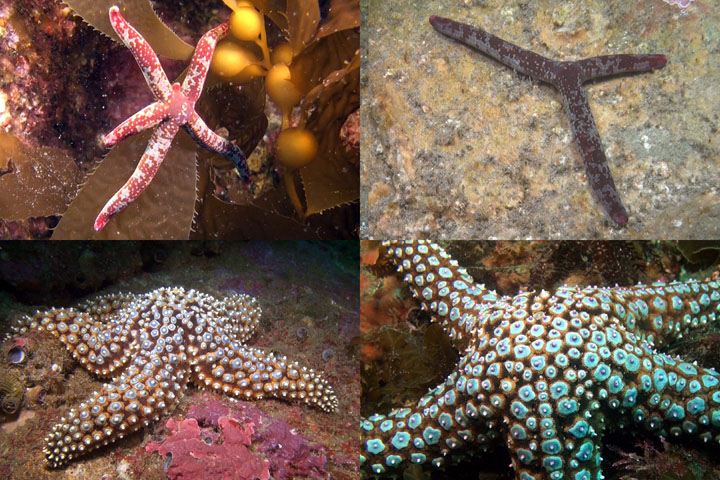

Not all sea star species disappeared during this recent event. One, the variable star (Linckia columbiae), did not seem to decline at all. I saw them frequently throughout the long warm water episode. The sea stars may have one to seven or more arms due to their reproductive strategy. Nancy Reagan would love them because they "just say no." Yep they reproduce primarily asexually by throwing off arms that grow into new stars. They feed on bacteria and organic detritus... yummy!

The species that I found disappeared most prominently in local waters was the giant spined or knobby sea star (Pisaster giganteus). I have observed this vicious predator chowing down on mussels, scallops, urchins, dead fish, etc. Once I even saw one engulf a group of seven mating Kellet whelks (snails). Sex can certainly be dangerous even in the marine world.

Due to my cancer I have been unable to dive for several months. I wondered when we would start to see a recovery in species like Pisaster. I happened to drive down to the dive park in the Dr. Bill Mobile II and encountered my good friend, local instructor Mark Guccione. He gave me the great news that he had finally seen one in the dive park. Maybe the recovery from this event is underway!

© 2017 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of over 700 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Five-armed (with bud) and three-armed variable stars; and giant spined sea star.

This column will not be about the return of Hollywood stars to the former Hotel St. Catherine (Catalina Island) like in the pre-War heyday. And despite the national interest in the recent total eclipse of the sun, I won't be writing about the heavenly bodies like Betelgeuse and Sirius. I've got another group of stars in mind today.

Those of my readers with good memories may think back to a column I wrote about the disastrous disappearance of most sea stars in waters ranging from the Pacific NW to SoCal. First noted way up north, it affected some 40 species of starfish (or sea stars for the PC crowd). The disease has been linked to a densovirus, and this is not the first time it has impacted sea stars and other echinoderms on the West Coast. It is often linked to unusually warm waters such as El Niños and the unusual Blobs that developed a few years ago.

The loss of these significant predators caused further imbalances in the ecology of waters so affected. Sea stars often prey on their cousins the sea urchins and help keep those populations in check. The waters up north were unusually warm, stressing populations of various kelp species. With the added threat of increased urchin numbers, this became a one-two punch for the kelp.

Down south in our local waters, several species of sea stars either disappeared or were present in noticeably lower numbers. Fortunately here in SoCal there are other predators like sheephead to control the populations of urchins. Many of the red and purple urchins also died off here as the warm water accelerates the impact of the same densovirus on them.

As an amateur astronomer, I love that the often dark skies of the island allow us to see many more stars than in downtown "Lost" Angeles. I also love that I can see stars underwater as well. After all, my mentor at Harvard (H. Barraclough Fell) was an echinoderm specialist. Over the last half century, I have experienced other warm water periods (mainly El Niños) when sea stars and sea urchins have largely disappeared. Fortunately they eventually return thanks to larvae that make it out to the island with the plankton and currents.

Not all sea star species disappeared during this recent event. One, the variable star (Linckia columbiae), did not seem to decline at all. I saw them frequently throughout the long warm water episode. The sea stars may have one to seven or more arms due to their reproductive strategy. Nancy Reagan would love them because they "just say no." Yep they reproduce primarily asexually by throwing off arms that grow into new stars. They feed on bacteria and organic detritus... yummy!

The species that I found disappeared most prominently in local waters was the giant spined or knobby sea star (Pisaster giganteus). I have observed this vicious predator chowing down on mussels, scallops, urchins, dead fish, etc. Once I even saw one engulf a group of seven mating Kellet whelks (snails). Sex can certainly be dangerous even in the marine world.

Due to my cancer I have been unable to dive for several months. I wondered when we would start to see a recovery in species like Pisaster. I happened to drive down to the dive park in the Dr. Bill Mobile II and encountered my good friend, local instructor Mark Guccione. He gave me the great news that he had finally seen one in the dive park. Maybe the recovery from this event is underway!

© 2017 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of over 700 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website Star Thrower Educational Multimedia (S.T.E.M.) Home Page

Image caption: Five-armed (with bud) and three-armed variable stars; and giant spined sea star.