"Only 20% of surgeons would like to use a checklist in their operations……but 94% would like one used in an operation on themselves…!"

Atul Gawande gave four presentations before Christmas as the 2014 Reith Lectures’ presenter (BBC iPlayer downloads and transcripts can be downloaded from here).

During these presentations, he highlighted ways in which the healthcare and medical industries could develop their safety further, but he also recognised that we are all human, fallible and therefore there was a limit to what could be achieved and, consequently we needed to recognise this when judging adverse outcomes. The same situation needs to be recognised within sports diving where we are undertaking an activity (of our choice) which has an inherent risk of fatality as we are in a hostile, non-life sustaining environment if something serious goes wrong.

His second presentation specifically looked at how better systems could improve safety, and radically reduce the mistakes and errors made, and improve performance. Some of you may have already read my articles about checklists and attended presentations I have given highlighting the need to have an established and positive culture to their use but you might be surprised to know that even in complex environments such as surgery, aviation and the oil and gas industry, they are not used when or as they are supposed to be

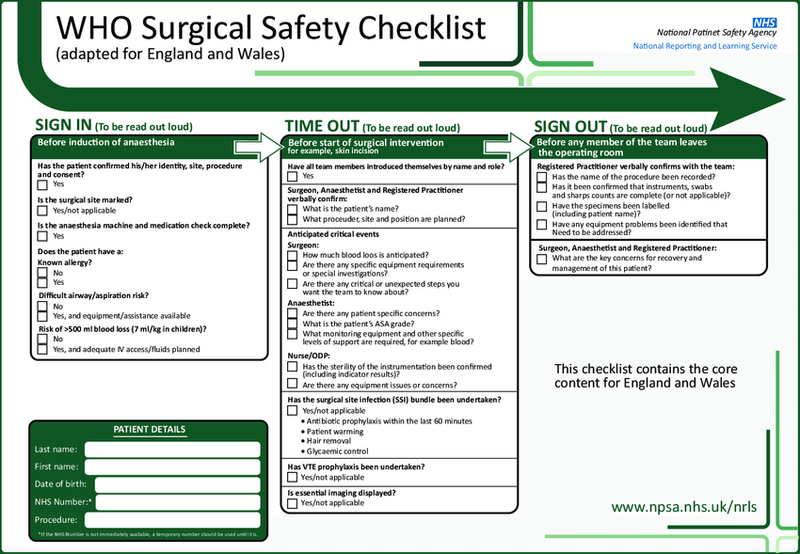

In Atul’s book, the Checklist Manifesto, he identifies that during a global study involving nearly 4000 patients, fatalities were reduced by 47%, adverse outcomes reduced by 36% and infections reduced by half through the use of a simple checklist like this (link to NHS site). This weekend I was chatting with Professor Simon Mitchell at the 6th Tech Diving Network conference in Germany where we were both presenting. Simon's team were part of this global study and he commented that if as much investment had been made into checklist design and deployment and other human factors interventions as drug research, then the millions of lives would have been saved. However, we also recognised that companies don't make money from such interventions!

You might think that such checklist items should not be required for surgery, but they were! You could ask the same about checks for an aircraft landing, why would you need to write a checklist to ensure you put the gear down? Pilots still miss them or don’t do them – they get complacent in what they are doing. Complacency has been defined as the mismatch between the model which the operator has and the real situation – things have changed and we haven’t noticed and recognised that they have.

So why shouldn’t we use a short, hard-copy checklist for rebreather diving or a cross-checked verbal checklist for areas where the risks are less? I can’t think of a good reason to be honest! Internet comments are often seen along the lines of “If you need a checklist to dive a CCR, then you shouldn’t be diving a CCR”. Same goes for other forms of diving. DAN did a study in 2012 on the use of checklists in recreational diving where they gave a checklist to one half of a boat and the other half could use a checklist if they wanted to. The results are available here and they stopped a number of divers getting into the water with incorrect equipment configurations. Did these prevent an incident from occurring, maybe. However, it only takes a series of unlinked situations to create that perfect storm and that gap in the Swiss Cheese Model opens up, allowing the incident to develop to maturity.

Animated Swiss Cheese Model from Human In the System on Vimeo.

I completed my Mod 1 on the JJ CCR in December 2014 and as part of that course the instructor required us to develop our own build and pre-dive checklists, refining the operational manual such that we were sure everything was in a safe configuration to dive using a checklist format that was usable (note: there is a science to developing checklists and they should simple (6-8 items per checklist) and no more than 2-3 mins to complete each checklist. I personally went further and developed the buddy pre-dive brief and wrote it down and would then read from this to make sure everything was covered from my perspective and to let my team know I had done the checks. This pre-brief format allowed me to capture everything I needed to action during the pre-breathe making sure the items/actions were as they were supposed to be before I read off the list of items in the brief – a checklist is useless if you don’t follow it and make sure the items are as they are. My instructor argued that I should be able to run through a brief from memory, using the equipment configuration (starting on the O2 side, working up to the top over the right-hand side, then down to the dil side valves and then back up over the top again) as a flow. My concern was that due to human behaviour and nature, we will likely miss things and each time we miss them and someone else doesn’t pick them up, we ‘accept’ that they are not required and will likely be forgotten on subsequent checks.

Checklists provide the operator with a structure to follow to ensure that the tasks are actually completed. Similarly, structured briefs ensure that both the communicator and the listener(s) know that everything has been covered that should have been because if the person giving the brief misses something, then the others can remind them. If a brief is haphazard, then the rest of the team do not know if something has been missed by accident or omitted on purpose. For those who solo dive, a checklist is even more important because when you commit an act of omission (a lapse in error management terms), then you will not know you’ve missed the item and there is no-one else to pick you up on it. That minor item may be inconsequential, but then again it might be the start of a chain of events which you won’t recognise until it is too late, or more recently from May 2018 here.

Why not use a checklist? Too proud? Might show that you are fallible to your peers? Takes too long? Too complicated? Surgeons use checklists to make sure they are amputating the correct limb! Fast jet pilots use checklists for things as simple as making sure the ejection seat pins are removed before getting airborne! The weird thing is that until the culture is established, then the mindset is 'checklists are for other people because they are fallible. But I am not like that.'

So What?

We cannot prevent all human error from occurring. However, by designed and deploying checklists which are fit for purpose (and not just liability limiting tools) then we can purposely slow divers down to ensure that critical information is passed on and equipment configurations are set the way they should be to support life. The problem with errors of omission (lapses), by definition we don't know we've missed a critical step. Checklists come in different shapes and sizes, but the ones I am talking about are approximately 5 steps long, completed immediately prior to getting in the water to ensure that your life support equipment will indeed provide life support.

===============================

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a training and coaching company focused on teaching and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.

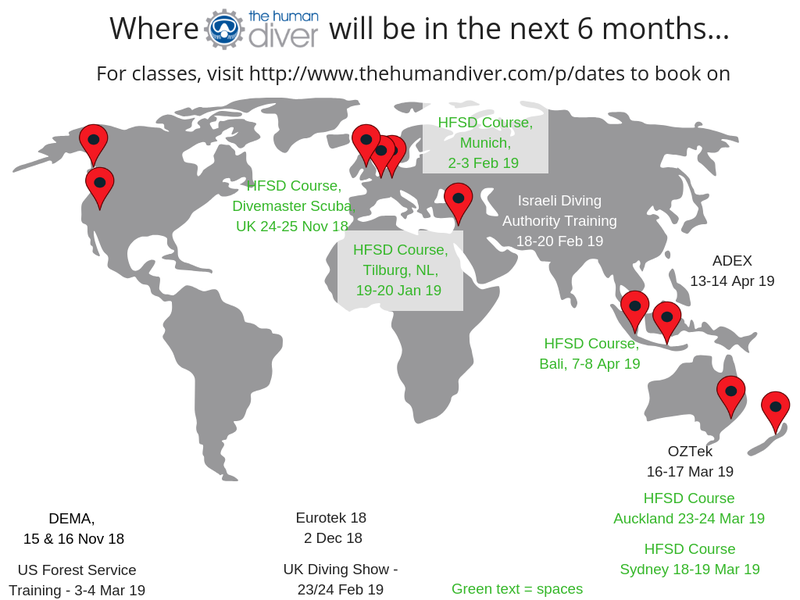

Forthcoming dates and conferences are below

Atul Gawande gave four presentations before Christmas as the 2014 Reith Lectures’ presenter (BBC iPlayer downloads and transcripts can be downloaded from here).

During these presentations, he highlighted ways in which the healthcare and medical industries could develop their safety further, but he also recognised that we are all human, fallible and therefore there was a limit to what could be achieved and, consequently we needed to recognise this when judging adverse outcomes. The same situation needs to be recognised within sports diving where we are undertaking an activity (of our choice) which has an inherent risk of fatality as we are in a hostile, non-life sustaining environment if something serious goes wrong.

His second presentation specifically looked at how better systems could improve safety, and radically reduce the mistakes and errors made, and improve performance. Some of you may have already read my articles about checklists and attended presentations I have given highlighting the need to have an established and positive culture to their use but you might be surprised to know that even in complex environments such as surgery, aviation and the oil and gas industry, they are not used when or as they are supposed to be

In Atul’s book, the Checklist Manifesto, he identifies that during a global study involving nearly 4000 patients, fatalities were reduced by 47%, adverse outcomes reduced by 36% and infections reduced by half through the use of a simple checklist like this (link to NHS site). This weekend I was chatting with Professor Simon Mitchell at the 6th Tech Diving Network conference in Germany where we were both presenting. Simon's team were part of this global study and he commented that if as much investment had been made into checklist design and deployment and other human factors interventions as drug research, then the millions of lives would have been saved. However, we also recognised that companies don't make money from such interventions!

You might think that such checklist items should not be required for surgery, but they were! You could ask the same about checks for an aircraft landing, why would you need to write a checklist to ensure you put the gear down? Pilots still miss them or don’t do them – they get complacent in what they are doing. Complacency has been defined as the mismatch between the model which the operator has and the real situation – things have changed and we haven’t noticed and recognised that they have.

So why shouldn’t we use a short, hard-copy checklist for rebreather diving or a cross-checked verbal checklist for areas where the risks are less? I can’t think of a good reason to be honest! Internet comments are often seen along the lines of “If you need a checklist to dive a CCR, then you shouldn’t be diving a CCR”. Same goes for other forms of diving. DAN did a study in 2012 on the use of checklists in recreational diving where they gave a checklist to one half of a boat and the other half could use a checklist if they wanted to. The results are available here and they stopped a number of divers getting into the water with incorrect equipment configurations. Did these prevent an incident from occurring, maybe. However, it only takes a series of unlinked situations to create that perfect storm and that gap in the Swiss Cheese Model opens up, allowing the incident to develop to maturity.

Animated Swiss Cheese Model from Human In the System on Vimeo.

I completed my Mod 1 on the JJ CCR in December 2014 and as part of that course the instructor required us to develop our own build and pre-dive checklists, refining the operational manual such that we were sure everything was in a safe configuration to dive using a checklist format that was usable (note: there is a science to developing checklists and they should simple (6-8 items per checklist) and no more than 2-3 mins to complete each checklist. I personally went further and developed the buddy pre-dive brief and wrote it down and would then read from this to make sure everything was covered from my perspective and to let my team know I had done the checks. This pre-brief format allowed me to capture everything I needed to action during the pre-breathe making sure the items/actions were as they were supposed to be before I read off the list of items in the brief – a checklist is useless if you don’t follow it and make sure the items are as they are. My instructor argued that I should be able to run through a brief from memory, using the equipment configuration (starting on the O2 side, working up to the top over the right-hand side, then down to the dil side valves and then back up over the top again) as a flow. My concern was that due to human behaviour and nature, we will likely miss things and each time we miss them and someone else doesn’t pick them up, we ‘accept’ that they are not required and will likely be forgotten on subsequent checks.

Checklists provide the operator with a structure to follow to ensure that the tasks are actually completed. Similarly, structured briefs ensure that both the communicator and the listener(s) know that everything has been covered that should have been because if the person giving the brief misses something, then the others can remind them. If a brief is haphazard, then the rest of the team do not know if something has been missed by accident or omitted on purpose. For those who solo dive, a checklist is even more important because when you commit an act of omission (a lapse in error management terms), then you will not know you’ve missed the item and there is no-one else to pick you up on it. That minor item may be inconsequential, but then again it might be the start of a chain of events which you won’t recognise until it is too late, or more recently from May 2018 here.

Why not use a checklist? Too proud? Might show that you are fallible to your peers? Takes too long? Too complicated? Surgeons use checklists to make sure they are amputating the correct limb! Fast jet pilots use checklists for things as simple as making sure the ejection seat pins are removed before getting airborne! The weird thing is that until the culture is established, then the mindset is 'checklists are for other people because they are fallible. But I am not like that.'

So What?

We cannot prevent all human error from occurring. However, by designed and deploying checklists which are fit for purpose (and not just liability limiting tools) then we can purposely slow divers down to ensure that critical information is passed on and equipment configurations are set the way they should be to support life. The problem with errors of omission (lapses), by definition we don't know we've missed a critical step. Checklists come in different shapes and sizes, but the ones I am talking about are approximately 5 steps long, completed immediately prior to getting in the water to ensure that your life support equipment will indeed provide life support.

===============================

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a training and coaching company focused on teaching and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.

Forthcoming dates and conferences are below