David Wilson

Contributor

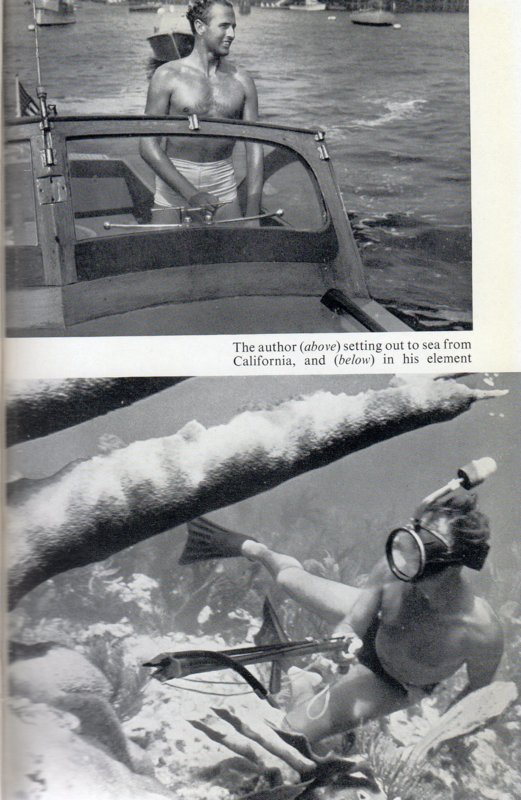

Today's topic is the Cressi range of snorkel-masks. Masks with built-in snorkels tend to polarise opinion. Many people think they were initially devised as a toy for children, who then risked their lives by ignoring safety advice about using them for surface observation only. This doesn't stand up to scrutiny, however, if we take the trouble to delve a little into their history. The most prolific early manufacturers of snorkel-masks operated in Spain, France and Italy on the coast of the Mediterranean sea, where their end-users engaged in spearfishing for recreation or profit. Extended periods spent floating face down on the surface watching for game meant inhaling and exhaling through a breathing tube whose mouthpiece would have strained the jaw, ached the teeth and inflamed the gums when held in the mouth during those lengthy sessions. A snorkel-mask enabling the spearfisher to shut his mouth and breathe normally through the nose must have been something of a godsend to many. So it was that a number of early 1950s underwater hunting books contained illustrations of experienced spearfishers wearing snorkel-masks, e.g.:

The above from Cornel Lumière (1956) Beneath the seven seas. London: Hutchinson.

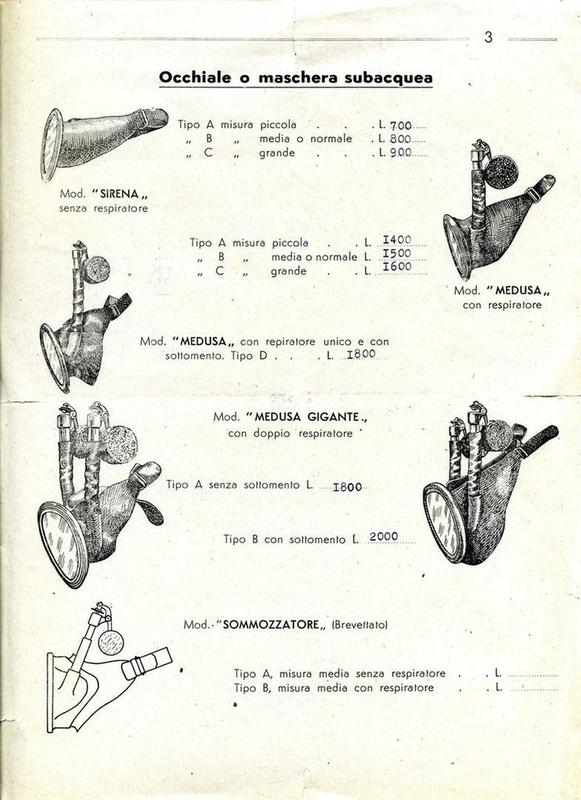

Bearing these circumstances in mind, it will come as less of surprise when I say that the 1947 Cressi catalogue featured no fewer than five images of snorkel-masks, while standalone snorkels were conspicuous by their absence:

And let's remember that the Cressi brothers were practising spearfishers, so they manufactured only what they deemed to be absolutely necessary for their own, and their clients', underwater hunting expeditions off the Genoese coast while enduring economic austerity and privations in the aftermath of World War II.

The first illustration at the top of the catalogue page shows the snorkel-less Cressi Sirena mask, which we reviewed earlier in this thread. We'll focus instead here on the quintet of late-1940s Cressi snorkel-masks. Take a moment to note the common features. Observe the long sidepieces and short headstraps, the breathing tubes with their cork-float operated valves at the top and their sockets at the bottom enabling access to the interior of the mask. And let us not forget that the designers of these perhaps quaint-looking devices really had no blueprint to go on other than their own imaginations and spearfishing experiences.

The above from Cornel Lumière (1956) Beneath the seven seas. London: Hutchinson.

Bearing these circumstances in mind, it will come as less of surprise when I say that the 1947 Cressi catalogue featured no fewer than five images of snorkel-masks, while standalone snorkels were conspicuous by their absence:

And let's remember that the Cressi brothers were practising spearfishers, so they manufactured only what they deemed to be absolutely necessary for their own, and their clients', underwater hunting expeditions off the Genoese coast while enduring economic austerity and privations in the aftermath of World War II.

The first illustration at the top of the catalogue page shows the snorkel-less Cressi Sirena mask, which we reviewed earlier in this thread. We'll focus instead here on the quintet of late-1940s Cressi snorkel-masks. Take a moment to note the common features. Observe the long sidepieces and short headstraps, the breathing tubes with their cork-float operated valves at the top and their sockets at the bottom enabling access to the interior of the mask. And let us not forget that the designers of these perhaps quaint-looking devices really had no blueprint to go on other than their own imaginations and spearfishing experiences.