Recently there have been a number of high profile incidents in diving in which the decisions made appear incredulous given the outcome. Using a phrase from Todd Conklin, a US-based high performance team developer and safety advocate, the outcomes whilst sad in many cases are not the most interesting part, it is the decision making process which led to them which is interesting. You could say that they are unsurprising or normal. In fact, in 1984 Chris Perrow wrote a book entitled ‘Normal Accidents’ in which he describes the facts that most of accidents in high risk operations are normal, in that we know they could happen, we just don’t know where and when, and given our limited personal and organisational capacity to process massive amounts of information, it is no surprise that they slip by our attention and we make flawed decisions. It is this combination of, often discrete decisions which leads to disaster.

That is what this blog post is about, decision making and why, in hindsight, we often view an adverse event with clarity compared to those who were involved at the time and why we are unable to rationalise their thought processes which lead to their demise.

I am not biased! Yes you are! We all are...

In the first part we will look at the key biases we are exposed to when it comes to examining adverse events. The first of these is hindsight bias. This is where we make the assumption that we knew what the outcome would have been if we had been placed in that same position, with the same information, training and environment/physical cues. It is incredibly difficult to isolate this bias and remove it from our thought process, other than by asking the simple question “Why did it make sense to those involved to behave in the manner they did?”

An example of this might be the close-call which the National Park Service Submerged Resource Centre team had 3 years ago when their chief scientist had an oxygen toxicity-induced seizure at 33m/110ft on their VR Technology Sentinel and was recovered by the buddy and dive team. The technical reason for the event was that two of the three oxygen cells were current limited and due to the voting logic within the system, the controller drove the pO2 in the loop up to more than 3.00. The reason they were current limited was because of their age and should have been replaced - they were 33 months old. You might ask why weren’t they replaced in a timely manner? The following provides a brief explanation in terms of decision making.

The team had been diving a mixture of AP Inspirations and VR Sentinels. The AP units had always had their cells replaced by AP when they went back for a service. The Sentinels when they went back for their service had come back with a test sheet saying the cells were operating at 100% to spec. The assumption on the part of the team was that the cells had been changed based on their previous experience with AP units; this in fact was not the case although they did have a note included in the units to say the cells should be changed every 18 months. In addition, the service had happened four months before the event so there is an ongoing assumption that the unit is good for another 8 months or so especially as the unit was not dived in the first 3 of those 4 months. Further, the day before the unit had performed flawlessly with no current limiting. In hindsight(!!), the team should have checked the cell dates before each dive, or at least during each unit assembly but they didn’t because their mental model of the world was different to reality. (This shortfall has been addressed since the event. In addition, there were many other issues which contributed to the event but have not been covered due to brevity of this article.)

This brings us nicely onto the next bias - outcome bias - and how we often judge the severity of the decision-making process based on the outcome we perceive. As another example, reflect on the following. A team of two full cave certified divers were travelling into a cave system where No 2 had been before but the lead diver hadn’t. After approximately 30 mins they passed through a cenote with amazing shafts of light shining down which took their attention away from the line whilst they kept swimming. After another 5 mins or so, the second diver started to get an uneasy feeling about where they were because the cave didn’t look right. He stopped, signalled the lead that something wasn’t right, turned around, swam back up the line and found the jump which they had swum over without realising it because their attention drawn to the shafts of light. Coincidentally, they had encountered another line just beyond theirs which because of their brief distraction, they followed because they had missed the jump. If the second diver had not been in that cave before, he would not have had that uneasy feeling and they would have carried on until something was really obviously wrong from the plan/brief or when they reached their gas turn pressures. Now consider what the narrative would have read if they had had an emergency which necessitated a gas-sharing blind exit and they reached the terminal point of the line which they were on and then had to conduct a ‘blind jump’ which they were unable to do, and as a consequence, drowned? The narrative would likely say “they conducted a jump without a line in place, how stupid, they broke a golden rule of cave diving!” In the first case it is also easy to say “they should have paid more attention” but the use of should have or could have does not help prevent future adverse events. How severe (and how prevalent) are such un-noticed blind jumps? After a quick chat with colleagues here in Helsinki at Techu2017, not that uncommon…

Decision making is complicated!

So if we have these major biases impacting our view of decision-making after the event, what informs us of our decisions during the activity.

It is complicated! It involves situational awareness, ‘decision making’ and a feedback loop to inform future decision-making strategies. It also involves the goals and objectives we are aiming for as this tunnels our view of the world, we primarily look for things which confirm our predicted outcomes. It involves our long term memories and the experiences we have built up through ‘life’, training and previous dives. It involves the equipment we are using and the environment we are in, and whether those are improving or removing our mental capacity. The diagram showing Endsley’s SA Model below shows the linkages in this decision-making and situational awareness. This is why SA is not just about what is going on around you right now, it is how we perceive and process the information and then an ability to project it into the future.

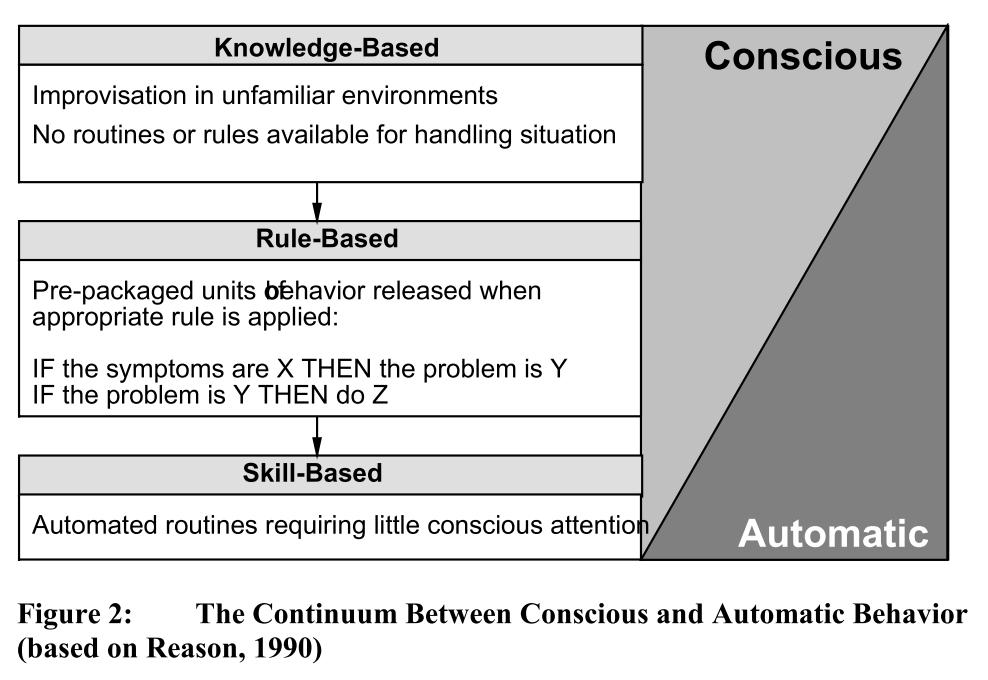

However, to simplify we have three key ways of making decisions: skills-based, rules-based and knowledge-based. The terms skill, rule and knowledge based information processing refer to the degree of conscious control exercised by the individual over his or her activities.

In the image below, knowledge-based refers to an almost completely conscious manner. In the case of a beginner diver, learning to put up a dSMB for the first time, they are solving the problem as they are going along, learning the steps which make up the skill. In the case of an experienced diver, this might be a novel situation such as being in a wreck and a small collapse happens and they have to problem solve dynamically. The skill based mode refers to the smooth execution of highly practiced, largely physical actions in which there is virtually no conscious monitoring.

Skill based responses are generally initiated by some specific event, e.g. the requirement to dump gas from the BCD as the diver ascends. The highly practiced operation of dumping the gas will then be executed largely without conscious thought. In highly skilled individuals, the error rates are in the order of 1:10 000. However, when we move to knowledge-based decision making where we have to use previous experiences to solve the problem and come up with a viable solution, then it drops to 1:2 - 1:10!