That’s quite disturbing to read once you process the technical facts …

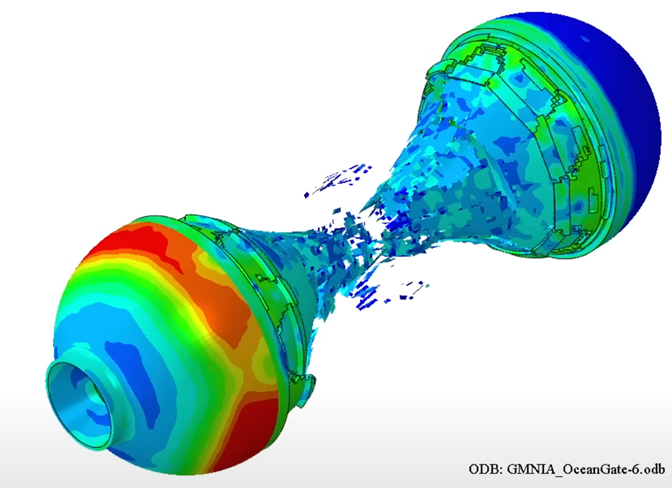

Simulation Reveals Exactly How Titan Submersible Imploded - Engineering.com

For the victims, no time to panic and a painless death.www.engineering.com

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Titanic tourist sub goes missing sparking search

- Thread starter Fastmarc

- Start date

Please register or login

Welcome to ScubaBoard, the world's largest scuba diving community. Registration is not required to read the forums, but we encourage you to join. Joining has its benefits and enables you to participate in the discussions.

Benefits of registering include

- Ability to post and comment on topics and discussions.

- A Free photo gallery to share your dive photos with the world.

- You can make this box go away

Dan

Contributor

Loring Chien, former principal engineer at Fortune 1000 company (2002-2016) answer this question in Quora Quest:

“Were the corpses of Titan Submarine found?”

His answer:

“It is very likely that the bodies were severely mangled by the implosion of the hull. The contents of the hull would have been crushed to about 1/400th the volume by the 6000 PSI of pressure. The inrushing water would be like a huge piston causing both enormous pressure rise and probable very high flash temperatures as the existing air was compressed in an instant.

They have said they recovered some human remains. What exactly they were and how small and what condition was thankfully not described.”

“Were the corpses of Titan Submarine found?”

His answer:

“It is very likely that the bodies were severely mangled by the implosion of the hull. The contents of the hull would have been crushed to about 1/400th the volume by the 6000 PSI of pressure. The inrushing water would be like a huge piston causing both enormous pressure rise and probable very high flash temperatures as the existing air was compressed in an instant.

They have said they recovered some human remains. What exactly they were and how small and what condition was thankfully not described.”

Dan

Contributor

It would be an interesting test by putting a dead animal skull (road-killed squirrel?) in a carbon fiber cylinder inside a pressure chamber full of water, pressure up the chamber into 6000 PSIg and let the carbon-fiber cylinder imploded and examining the remains. I bet they are till intact.Wonder how teeth do in a situation like that.

Easier to just place the rabbit in a 3 ton hydraulic press and see what happens. I don't think it would look much like a rabbit after.It would be an interesting test by putting a dead animal skull (road-killed squirrel?) in a carbon fiber cylinder inside a pressure chamber full of water, pressure up the chamber into 6000 PSIg and let the carbon-fiber cylinder imploded and examining the remains. I bet they are till intact.

Dan

Contributor

May be the skull would crush, but we are talking about the teeth?Easier to just place the rabbit in a 3 ton hydraulic press and see what happens. I don't think it would look much like a rabbit after.

Wookie

Proud to be a Chaos Muppet

Staff member

ScubaBoard Business Sponsor

ScubaBoard Supporter

Scuba Instructor

Hit a tooth with a hammer and see how much tooth is leftMay be the skull would crush, but we are talking about the teeth?

Dan

Contributor

When you hit a tooth with a hammer, the force applied from one direction. Hydraulic force comes from all directions. That’s why spherical objects are the strongest structures as the force comes from all directions towards a point at the center of the objects. So, pounding it with a hammer is not the same as hydraulic force.Hit a tooth with a hammer and see how much tooth is left

Wookie

Proud to be a Chaos Muppet

Staff member

ScubaBoard Business Sponsor

ScubaBoard Supporter

Scuba Instructor

Although crushing bodies within a collapsing pressure vessel is more akin to crushing a tooth between a hammer and anvil than just subjecting a body to hydraulic pressure.When you hit a tooth with a hammer, the force applied from one direction. Hydraulic force comes from all directions. That’s why spherical objects are the strongest structures as the force comes from all directions towards a point at the center of the objects. So, pounding it with a hammer is not the same as hydraulic force.

Maybe, but there is a bunch of energy released and I'm betting on high temperatures.It would be an interesting test by putting a dead animal skull (road-killed squirrel?) in a carbon fiber cylinder inside a pressure chamber full of water, pressure up the chamber into 6000 PSIg and let the carbon-fiber cylinder imploded and examining the remains. I bet they are till intact.