Some of you know that I have been spending most of my free time over the past few months working on the Falmouth-Cathedral Springs project, which is a joint project between Karst Underwater Research (KUR) and the Woodville Karst Plains Project (WKPP). I will be writing up a lengthy article in the near future, but Cathedral Canyon is an extensive system which was made famous by Sheck Exley for setting a world record distance penetration in the system, an entire chapter in

Caverns Measureless to Man is dedicated to this system.

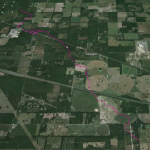

However, the system is also very important as a lesson in how agriculture and development can impact our water resources. The system connects to the Suwannee River at Ellaville Spring, and trends east several miles past the town of Falmouth. The system cuts underneath a chicken processing plant and several farms from the source on it’s way towards the river.

Current exploration of Cathedral has put the cave system out approximately 19,000′ from the nearest entrance. To say that exploration in this system is a challenge would be an understatement, in addition to the large distances from the nearest exit, the visibility tends to run 15′ and the depths vary throughout the system from 70′ to 185′, which can cause sinus problems, in addition to wasting precious inflation gas.

Underwater cave survey is conducted by a simple method – you install a line with knots every 10′ during exploration, and on exit take the azimuth reading every time the system changes direction, and count the knots. Although this system works relatively well, when you start talking distances on the order of 2-3 miles, minor errors can be magnified. A 1 or 2% error in the azimuth, plus a 3-4″ error in the distance for the knots, can put the cave survey off by up to a 1/4 mile at these distances.

This past weekend, on December 12th, we decided to validate and shore up the survey data by placing radio location beacons in the cave system at 6000′ and 10,200′ penetration. On the surface we then identified where the beacons were placed by using radio locators, which essentially allow us to triangulate in on the signal emitted by the beacons. This did two things for us: it allowed us to validate the survey, and it also gave us proof that the system runs under the spray fields. Additionally, I believe this may be the furthest distance that anyone has successfully deployed and used an underwater radio location beacon.

Here is the impressive thing we discovered: at a distance of 10,200′, Sheck Exley’s survey was off by only 80′. That’s less than a 0.8% error rate — incredibly impressive given that he used 1980’s era technology when he did his exploration.

This weekend would not have been possible without the help of a great team of people. Derek Ferguson needs to be given a lot of credit for coming up with the initial idea for the project, and proposing to do a radio locate at those distances. Jon Bernot and Charlie Roberson have been driving forces for the project, as well as performing some amazing new exploration. Ted McCoy has been an incredibly reliable member of the team — working out logistics in long range exploration, getting the habitat ready, or ready to hop in the water for a 7 hour excursion. Howard Smith has been a silent but steady assistant, always ready to lend a hand and never complaining of the work asked of him. And of course, Andy Pitkin has done an amazing job of converting the raw survey data into a usable format, and organizing and conducting the radio location beacons.