DIVE DRY WITH DR. BILL #819: DON'T OVERLOOK THE SMALL STUFF

Although they may not know it, both divers and land lubbers combing our beaches may be aware of the species I'm focusing on today. It frequently establishes on kelp blades once they've stopped their rapid growth and stabilized. It also may be found on rocks in the subtidal and even on the shells and occasionally exoskeletons of marine invertebrates. However, despite being incredibly common in our waters, it is too often overlooked due to its small size.

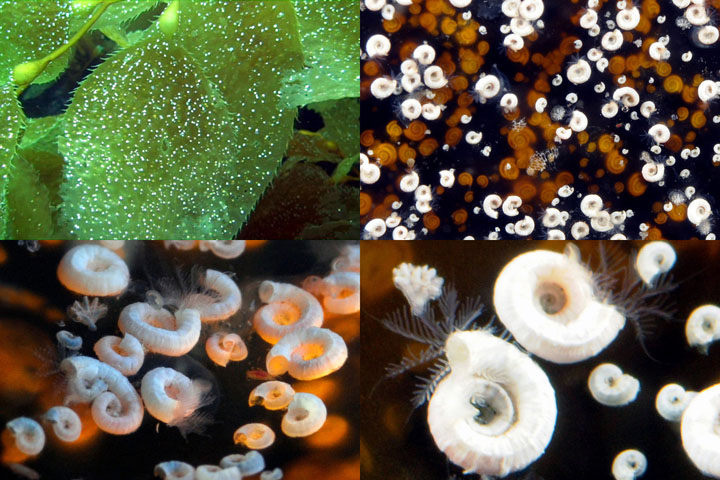

I'm referring to a tiny worm with a bright white shell that is abundant on older kelp blades (including those washed up on our beaches) and other substrates. Those of us with less than perfect vision may need a magnifying glass or microscope to see them clearly. It has been with us since some time in the Miocene (about 23 to 5 million years ago), although Homo sapiens didn't appear until between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago).

Our hominid ancestors like Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis were hanging around before then and "we" apparently mixed it up with them in "romance" (and probably combat) when "we" appeared so there may have been a few ancient marine biologists who noticed them. After all, kelp first appeared back in the late Miocene as well so the tiny worms were most likely present on it as well.

This tiny but very common worm is in the genus Spirorbis which one source listed as containing over twenty different species and another several hundred!. I guess it depends on which taxonomist you believe. I first encountered the genus in the waters off New Hampshire back in the mid-1960s during a Harvard marine biology field trip with my mentor Dr. Barry Fell. That one was S. borealis which is found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. It usually takes a worm specialist to tell the species apart. To make it even more difficult, some species have invaded the eastern Pacific from other regions of the globe. Due to the difficulty in identifying the individual species, many biologists simply refer to them by the genus name, Spirorbis sp.

The tiny tubes are just a few (1-4) millimeters in diameter. In some species the tube curls counter-clockwise and they are referred to as sinistral. Interesting that left is considered sinister by some. Others do coil in a clockwise or right handed direction (dextral). I guess those are the good guys. The thorax is larger but the abdomen is relatively small. Hmm, given the size of the worm I'd say everything is small! There are 10 setae or bristles extending from the anterior region which are used for feeding on plankton and organic detritus. One has a broadened operculum or trap door to seal the tube up when the worm withdraws into the shell. This serves as a defense against predators and to keep the worm moist when it is exposed to air.

I know eall my readers are dying to know about the sex life of Spirorbis worms. My research indicates that the Atlantic species I observed, S. borealis, is an hermaphrodite like most species of Spirorbis. The forward abdominal segments are male while the rear ones are female. The gonads mature about the same time and sperm is released outside of the body but inside the worm's tube. Some of these hermaphrodites fertilize themselves while others utilize cross-fertilization. Other species release their gametes into the water outside their shell, which is undoubtedly successful given the high density of the species. Some even brood the young inside the shell. At least one species (Spirorbis spirorbis) captures and stores sperm allowing it to fertilize the eggs at a later date. This eliminates the need to synchronize spawning. Upon fertilization the resulting larvae drift in the currents with the plankton, often for just a short time (as little as a few minutes), seeking a suitable spot to settle.

Some species reproduce year-round while others exhibit seasonal peaks. Scientists believe such peaks may be attributed to changes in water temperature or tidal changes. I know that when our waters are very cold, I am much more in the mood to cuddle after a dive. However, I haven't sensed any reaction to the tides... just the full moon when my fangs tend to elongate and I head out about midnight.

© 2019 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of over 800 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website http://www.starthrower.org

Image caption: Spirorbis tube worms on kelp blade (upper left) and images by Kevin Lee showing increasingly close-up details.

Although they may not know it, both divers and land lubbers combing our beaches may be aware of the species I'm focusing on today. It frequently establishes on kelp blades once they've stopped their rapid growth and stabilized. It also may be found on rocks in the subtidal and even on the shells and occasionally exoskeletons of marine invertebrates. However, despite being incredibly common in our waters, it is too often overlooked due to its small size.

I'm referring to a tiny worm with a bright white shell that is abundant on older kelp blades (including those washed up on our beaches) and other substrates. Those of us with less than perfect vision may need a magnifying glass or microscope to see them clearly. It has been with us since some time in the Miocene (about 23 to 5 million years ago), although Homo sapiens didn't appear until between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago).

Our hominid ancestors like Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis were hanging around before then and "we" apparently mixed it up with them in "romance" (and probably combat) when "we" appeared so there may have been a few ancient marine biologists who noticed them. After all, kelp first appeared back in the late Miocene as well so the tiny worms were most likely present on it as well.

This tiny but very common worm is in the genus Spirorbis which one source listed as containing over twenty different species and another several hundred!. I guess it depends on which taxonomist you believe. I first encountered the genus in the waters off New Hampshire back in the mid-1960s during a Harvard marine biology field trip with my mentor Dr. Barry Fell. That one was S. borealis which is found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. It usually takes a worm specialist to tell the species apart. To make it even more difficult, some species have invaded the eastern Pacific from other regions of the globe. Due to the difficulty in identifying the individual species, many biologists simply refer to them by the genus name, Spirorbis sp.

The tiny tubes are just a few (1-4) millimeters in diameter. In some species the tube curls counter-clockwise and they are referred to as sinistral. Interesting that left is considered sinister by some. Others do coil in a clockwise or right handed direction (dextral). I guess those are the good guys. The thorax is larger but the abdomen is relatively small. Hmm, given the size of the worm I'd say everything is small! There are 10 setae or bristles extending from the anterior region which are used for feeding on plankton and organic detritus. One has a broadened operculum or trap door to seal the tube up when the worm withdraws into the shell. This serves as a defense against predators and to keep the worm moist when it is exposed to air.

I know eall my readers are dying to know about the sex life of Spirorbis worms. My research indicates that the Atlantic species I observed, S. borealis, is an hermaphrodite like most species of Spirorbis. The forward abdominal segments are male while the rear ones are female. The gonads mature about the same time and sperm is released outside of the body but inside the worm's tube. Some of these hermaphrodites fertilize themselves while others utilize cross-fertilization. Other species release their gametes into the water outside their shell, which is undoubtedly successful given the high density of the species. Some even brood the young inside the shell. At least one species (Spirorbis spirorbis) captures and stores sperm allowing it to fertilize the eggs at a later date. This eliminates the need to synchronize spawning. Upon fertilization the resulting larvae drift in the currents with the plankton, often for just a short time (as little as a few minutes), seeking a suitable spot to settle.

Some species reproduce year-round while others exhibit seasonal peaks. Scientists believe such peaks may be attributed to changes in water temperature or tidal changes. I know that when our waters are very cold, I am much more in the mood to cuddle after a dive. However, I haven't sensed any reaction to the tides... just the full moon when my fangs tend to elongate and I head out about midnight.

© 2019 Dr. Bill Bushing. For the entire archived set of over 800 "Dive Dry" columns, visit my website http://www.starthrower.org

Image caption: Spirorbis tube worms on kelp blade (upper left) and images by Kevin Lee showing increasingly close-up details.